From Tadias archive (updated: August 9, 2008)

From Tadias archive (updated: August 9, 2008)

Tadias Magazine

By Ayele Bekerie, PhD

Aug 9, 2008

New York (TADIAS) – In his recent song dedicated to the Ethiopian Millennium and entitled Musika Heiwete (Music is My Life), the renowned Ethiopia’s rising pop singer, Teddy Afro, traces the geneaology of his music to classical Zema or chant compositions of St. Yared, the great Ethiopian composer, choreographer and poet, who lived in Aksum almost 1500 years ago.

Teddy, who is widely known for his songs mixed with reggae rhythms and local sounds, heart warming and enlightening lyrics, shoulder shaking and foot stomping beats, blends his latest offering with sacred musical terms, such as Ge’ez, Izil, and Ararary, terms coined by St. Yared to represent the three main Zema compositions.

In so doing, he is echoing the time tested and universalized tradition of modernity that has been pioneered and institutionalized by Yared. Teddy seems to realize the importance of seeking a new direction in Ethiopian popular music by consciously establishing links to the classical and indigenous tradition of modernity of St. Yared. In other words, Teddy Afro is setting an extraordinary example of reconfiguring and contributing to contemporary musical tradition based on Yared’s Zema.

Teddy Afro

An excellent example of what I call tradition of modernity, a tradition that contains elements of modernity or the perpetuation of modernity informed by originative tradition, is the annual celebration of St. Yared’s birthday in Debre Selam Qidist Mariam Church in Washington D.C. in the presence of a large number of Ethiopian Americans.

The Debteras regaled in fine Ethiopian costume that highlights the tri-colors of the Ethiopian flag, accompanied by tau-cross staff, sistra and drum, have chanted the appropriate Zema and danced the Aquaquam or sacred dance at the end of a special mass – all in honor of the great composer.

The purpose of this article is to narrate and discuss the life history and artistic accomplishments of the great St. Yared. We argue that St Yared was a great scholar who charted a modernist path to Ethiopian sense of identity and culture. His musical invention, in particular, established a tradition of cultural dynamism and continuity.

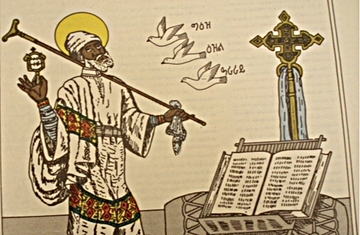

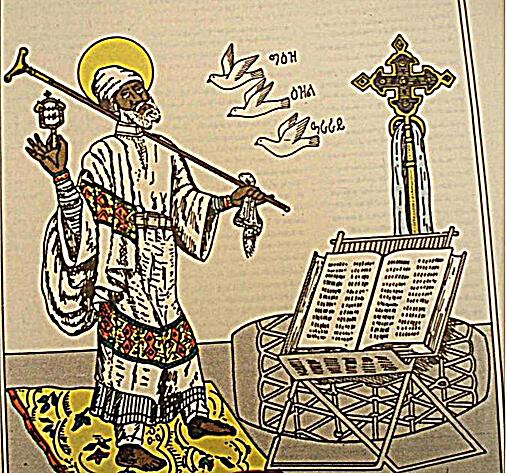

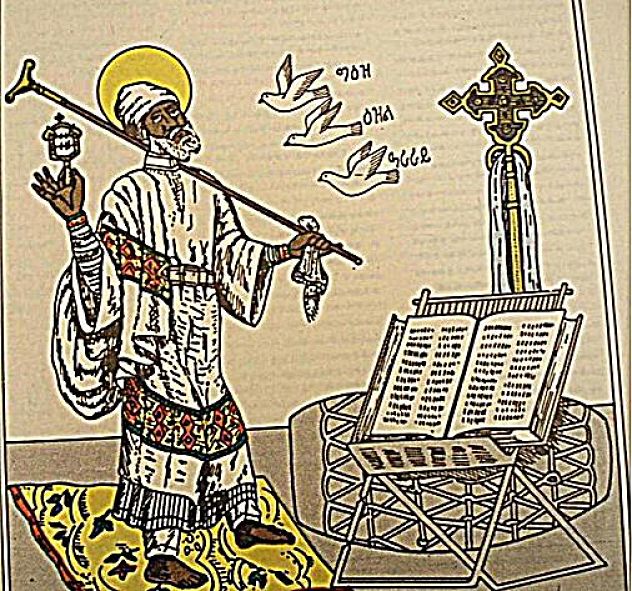

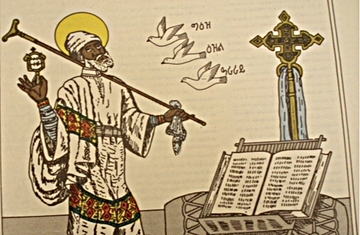

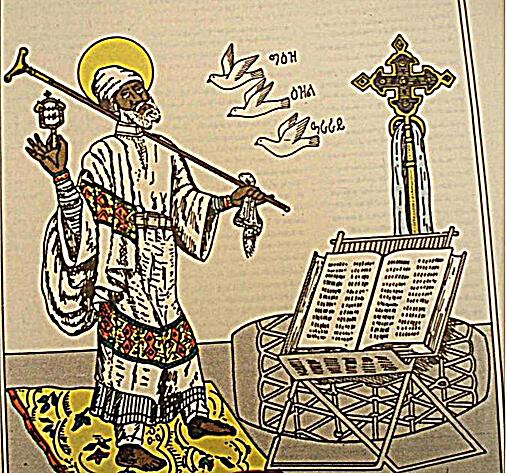

Figure 1: An artist rendering of St Yared while chanting Zema accompanied by sistrum, tau-cross staff. The three main zema chants of Ge’ez, Izil, and Araray which are represented by three birds. Digua, a book of chant, atronse (book holder), a drum, and a processional cross are also seen here. Source: Methafe Diggua Zeqidus Yared. Addis Ababa: Tensae Printing Press, 1996.

Zema or the chant tradition of Ethiopia, particularly the chants of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, is attributed to St. Yared, a composer and a choreographer who lived in Aksum in the 6th century AD. He is credited for inventing the zema of the Church; the chant that has been in use continuously for the last almost 1500 years.

It is indeed a classical tradition both musically and culturally. St Yared’s chants are characterized as subtle, spiritually uplifting, and euphonic. St Yared’s composition draws its fame both in its endurance and institutionalization of a tradition to mark the rhythm of life, the life of the faithful.

By composing chants for all natural and spiritual occasions, St. Yared has also laid down the foundation for common purpose and plurality among various ethnic, linguistic and regional groupings of the Ethiopian people. Elaborate visual representation of chants, the introduction of additional musical instruments, movements and performances by Ethiopian scholars have further enriched and secured the continuity and dynamism of the tradition to the present.

Furthermore, the music has become the central defining ritualistic feature of all the major fasts and feasts, appropriately expressing and performing joys and sorrows with the faithful in the or outside of the Church.

Saint Yared, the great Ethiopian scholar, was born on April 5, 501 A.D. in the ancient city of Aksum. His father’s name was Adam, whereas his mother’s name was Tawkelia. He descended from a line of prominent church scholars. At the age of six, a priest named Yeshaq was assigned as his teacher. However, he turned out to be a poor learner and, as a result, he was sent back to his parents. While he was staying at home, his father passed away and his mother asked her brother, Aba Gedeon, a well known priest-scholar in the church of Aksum Zion, to adopt her son and to take over the responsibility regarding his education.

Aba Gedeon taught The Old and New Testaments. He also translated these and other sacred texts to Ge’ez from Greek, Hebrew and Arabic sources. Even if Aba Gedeon allowed St. Yared to live and study with him, it took him a long time to complete the study of the Book of David. He could not compete with the other children, despite the constant advice he was receiving from his uncle. In fact, he was so poor in his education, kids used to make fun of him. His uncle was so impatient with him and he gave him several lashes for his inability not to compete with his peers.

Realizing that he was not going to be successful with his education, Yared left school and went to Medebay, a town where his another uncle resided. On his way to Medebay, not far from Aksum, he was forced to seek shelter under a tree from a heavy rain, in a place called Maikrah. While he was standing by leaning to the tree, he was immersed in thoughts about his poor performance in his education and his inability to compete with his peers. Suddenly, he noticed an ant, which tried to climb the tree with a load of a seed. The ant carrying a piece of food item made six attempts to climb the tree without success. However, at the seventh trial, the ant was able to successfully climb the tree and unloaded the food item at its destination. Yared watched the whole incident very closely and attentively; he was touched by the determined acts of the ant. He then thought about the accomplishment of this little creature and then pondered why he lacked patience to succeed in his own schooling.

He got a valuable lesson from the ant. In fact, he cried hard and then underwent self-criticism. The ant became his source of inspiration and he decided to return back to school. He realized the advice he received from his uncle was a useful advice to guide him in life. He begged Aba Gedeon to forgive him for his past carelessness. He also asked him to give him one more chance. He wants all the lessons and he is ready to learn.

His teacher, Aba Gedeon then began to teach him the Book of David. Yared not only was taking the lessons, but every day he would stop at Aksum Zion church to pray and to beg his God to show him the light. His prayer was answered and he turned out to be a good student. Within a short period of time, he showed a remarkable progress and his friends noticed the change in him. They were impressed and started to admire him. He completed the Old and New Testaments lessons at a much faster pace. He also finished the rest of lessons ahead of schedule and graduated to become a Deacon. He was fluent in Hebrew and Greek, apart from Ge’ez. Yared became as educated as his uncle and by the young age of fourteen, he was forced to assume the position of his uncle when he died.

Yared’s Zema is mythologized and sacralized to the extent that the composition is seen as a special gift from heaven. One version of the mythology is presented in Ethiopian book Sinkisar, a philosophical treatise, as follows: “When God sought praise on earth, he sent down birds from heaven in the images of angels so that they would teach Yared the music of the heavens in Ge’ez language. The birds sang melodious and heart warming songs to Yared. The birds noticed that Yared was immersed in their singing and then they voiced in Ge’ez:

“O Yared, you are the blessed and respected one; the womb that carried you is praised; the breasts that fed you the food of life are praised.”

Yared was then ascended to the heavens of the heaven, Jerusalem, where twenty-four scholars of the heaven conduct heavenly choruses. St Yared listened to the choruses by standing in the sacred chamber and he committed the music to memory. He then started to sing all the songs that he heard in the sacred chambers of the heaven to the gathered scholars. He then descended back to Aksum and at 9 a.m. (selestu saat) in the morning, inside the Aksum Zion church, he stood by the side of the Tabot (The Arc of the Covenant), raised his hands to heaven, and in high notes, which later labeled Mahlete Aryam (the highest), he sang the following:

“hale luya laab, hale luya lewold, hale luya wolemenfes qidus qidameha letsion semaye sarere wedagem arayo lemusse zekeme yegeber gibra ledebtera.”

With his song, he praised the natural world, the heavens and the Zion. He called the song Mahlete Aryam, which means the highest, referring to the seventh gates of heaven, where God resides. Yared, guided by the Holy Spirit, he saw the angels using drums, horns, sistra, Masinko and harp and tau-cross staff instruments to accompany their songs of praise to God, he decided to adopt these instruments to all the church music and chants.

The chants are usually chanted in conjunction with aquaquam or sacred dance. The following instruments are used for Zema and aquaquam combination: Tau-cross staff, sistra and drum. St Yared pioneered an enduring tradition of Zema. Aquaquam and Qene. These are musical, dance and literary traditions that continue to inform the spiritual and material well being of a significant segment of the Ethiopian population.

It is important to note that, as Sergew Hable Selassie noted “most of Yared’s books have been written for religious purposes.” As a result, historical facts are interspersed with religious sentiments and allegorical renderings.

According to Ethiopian legend, St.Yared obtained the three main Zema scores from three birds. These scores that Yared named Ge’ez, Izil, and Araray were revealed to him as a distraction from a path of destruction. According to oral tradition, Yared was set to ambush a person who repeatedly tried to cheat on his wife. In an attempt to resolve such vexing issue, he decided to kill the intruder. At a place where he camped out for ambush, three birds were singing different melodies. He swiftly lent his ears to the singing. He became too attracted to the singing birds. As a result, he abandoned his plan of ambush. Instead, he began to ponder how he could become a singer like the birds. Persistent practice guided by the echo of the melodies of the birds, fresh in his memory, ultimately paid off. Yared transformed himself to a great singer and composer as well as choreographer. Yared prepared his Zema composition from 548 to 568 AD. He had taught for over eleven years as an ordained priest.

Yared’s zema chants have established a classic Zema Mahlet tradition, which is usually performed in the outer section of the Church’s interior. The interior has three parts. The Arc of the Covenant is kept in Meqdes or the holiest section.

EMPEROR GEBRE MESQEL, THE CULTURAL PHILANTHROPIST

The Ethiopian emperor of the time was Emperor Gebre Mesqel (515-529), the son of the famous Emperor Kaleb, who in successfully, though briefly, reunited western and eastern Ethiopia on both sides of the Red Sea in 525 AD.

Emperor Gabra Masqal was a great supporter of the arts; he particularly established a special relationship with St. Yared, who was given unconditional and unlimited backing from him. The Emperor would go to church to listen to the splendid chants of St. Yared.

The Emperor was ruling at the peak of Aksumite civilization. He consolidated the gains made by his father and consciously promoted good governance and church scholarship. Furthermore, he presided over a large international trade both from within and without Africa.

According to Ethiopian history, Emperor Gabra Mesqel built the monastery of Debre Damo in Tigray, northern Ethiopia in the sixth century AD. It is the site where one of the nine saints from Syria, Abuna Aregawi settled. St Yared visited and performed his Zema at the monastery. The chants and dance introduced by Yared at the time of Gebra Mesqel are still being used in all the churches of Ethiopia, thereby establishing for eternity a classical and enduring tradition.

ST YARED’S MUSICAL COMPOSITION

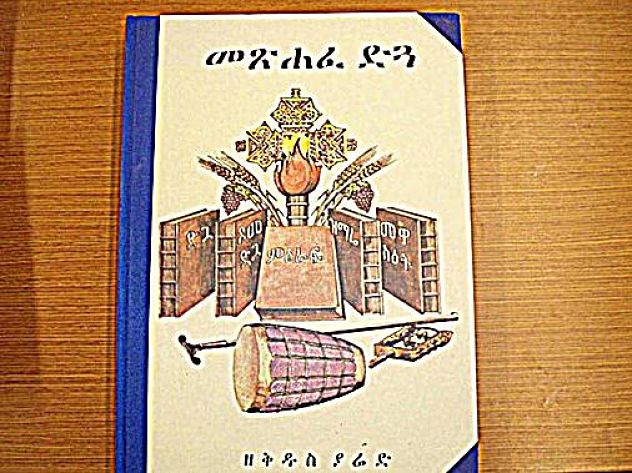

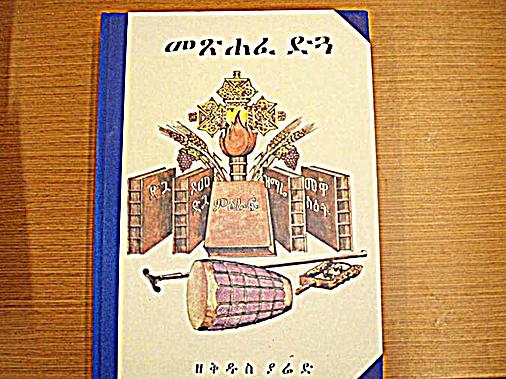

St Yared created five volumes of chants for major church related festivals, lents and other services and these volumes are:

The Book of Digua and Tsome Digua, the book of chants for major church holidays and Sundays, whereas the book of Tsome Digua contain chants for the major lent (fasting) season (Abiy Tsom), holidays and daily prayer, praise and chant procedures.

Digua is derived from the word Digua, which means to write chants of sorrow and tearful songs. Digua sometimes is also called Mahelete Yared or the songs of Yared, acknowledging the authorship of the chants to Yared. Regarding Digua’s significance Sergew Hable Selassie writes, “Although it was presented in the general form of poetry, there are passages relating to theology, philosophy, history and ethics.”

The Book of Meraf, chants of Sabat, important holidays, daily prayers and praises; also chants for the month of fasting.

The Book of Zimare, contain chants to be sang after Qurban (offerings) that is performed after Mass. Zemare was composed at Zur Amba monastery.

The Book of Mewasit, chants to the dead. Yared composed Mewasit alongside with Zimare.

The Book of Qidasse, chants to bless the Qurban (offerings).

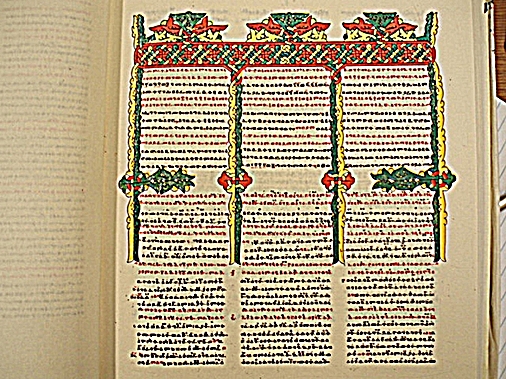

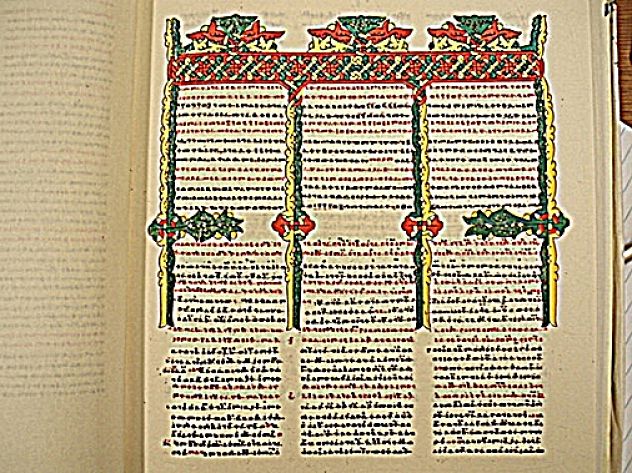

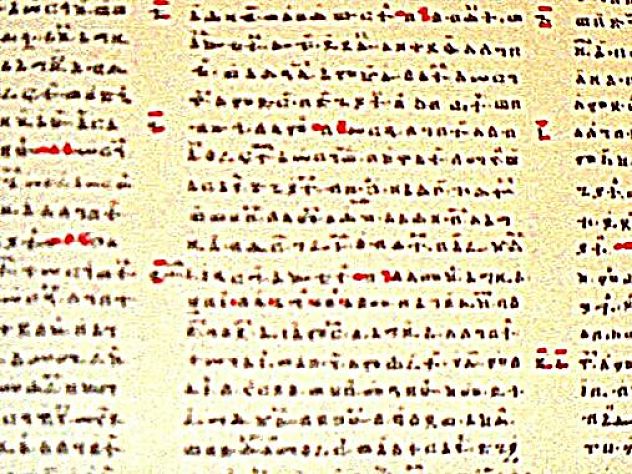

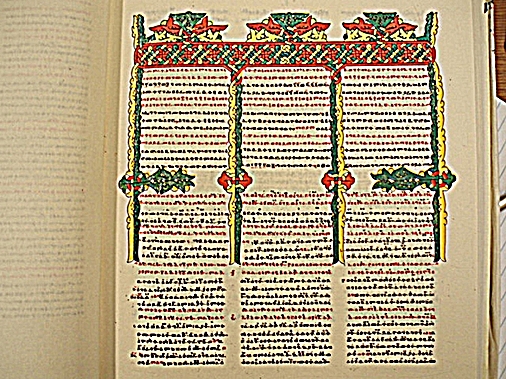

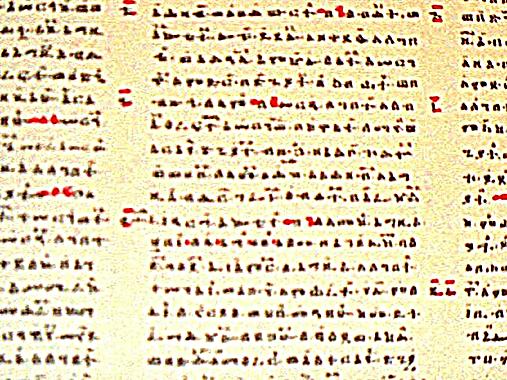

Figure 2. An illustrated Zema chant text and notes from the Book of Digua (Metshafe Digua Zeqidus Yared), p. 3.

Yared completed these compositions in nine years. All his compositions follow the three musical scales (kegnit), which he used to praise, according to Ethiopian tradition, his creator, who revealed to him the heavenly chants of the twenty-four heavenly scholars.

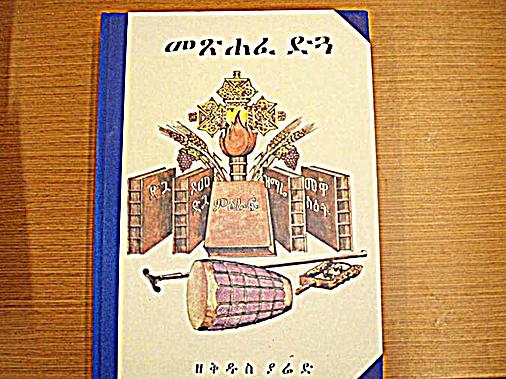

Figure 3. The front cover of Metshafe Digua Zeqidus Yared (Book of Digua). The cover shows the five volumes of Yared’s Zema composition: Digua, Tsome Digua, Miraf, Zimare, and Mewasit. Processional Ethiopian cross, drum, sistrum, and tau-cross staff are also illustrated in the cover.

Each of these categories are further classified with three musical scales (Kegnitoch) that are reported to contain all the possible musical scales:

Ge’ez, first and straight note. It is described in its musical style as hard and imposing. Scholars often refer to it as dry and devoid of sweet melody.

Izel, melodic, gentle and sweet note, which is often chanted after Ge’ez. It is also described as affective tone suggesting intimation and tenderness.

Ararai, third and melodious and melancholic note often chanted on somber moments, such as fasting and funeral mass.

Musical scholars regard these scales as sufficient to encompass all the musical scores of the world. These scales are sources of chants or songs of praise, tragedy or happiness. These scales are symbolized as the father, the son and the Holy Spirit in the tradition.

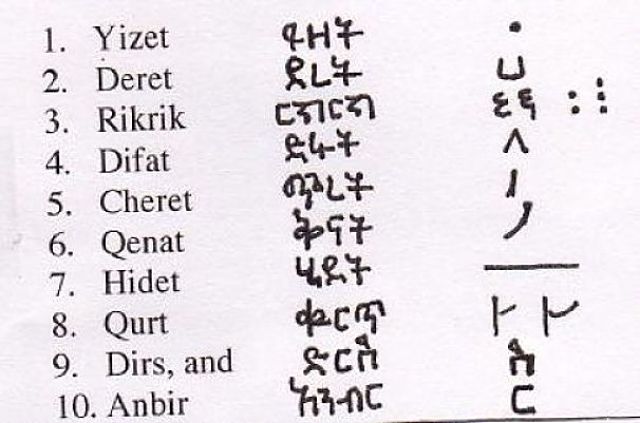

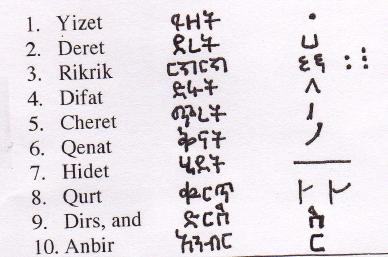

The composer Yared wrote the notes of the Digua on parchment and he also composed ten musical notations. The notations were fully developed as musical written charts in the 17th century AD. This took place much earlier than the composition of the musical note using seven alphabetic letters within the Western tradition. St Yared named the ten musical notations as follows: Yizet, Deret, Rikrik, Difat, Cheret, Qenat, Hidet, Qurt, Dirs, and, Anbir.

The ten notations have their own styles of arrangement and they are collectively called Sirey, which means lead notations or roots to chants. The notations are depicted with lines or chiretoch (marks).

Names and signs of St. Yared zema chant. The names are written in Ge’ez in the second column. The signs are in the third column.

According to Lisane Worq Gebre Giorgis, Zema notes for Digua were fully developed in the 16th century AD by the order of Atse Gelawedos. The composers were assembled in the Church of Tedbabe Mariam, which was led by Memhir Gera and Memhir Raguel. The chants, prior to the composition of notations, learned and studied orally. In other words, the chants were sang and passed on without visual guidance. Oral training used to take up to 70 years to master all the chants, such as Digua (40 years), Meraf (10 years), Mewasit (5 years), Qidasse (10 years), and Zimare (15 years). The chant appeared in the written form made it easier for priests to study and master the various chants within a short period of time.

The ten Zemawi notations are designed to correspond with the ten commandments of Genesis and the ten strings of harp. The notes, however, were not restricted to them. In addition, they have developed notations known as aganin, seyaf, akfa, difa, gifa, fiz, ayayez, chenger, mewgat, goshmet, zentil, aqematil, anqetqit, netiq, techan, and nesey.

The composition of the Digua Zema chant with notations took seven years, whereas mewasit’s chants were completed in one year, zemare’s in two years, qidasse in two years, and meraf remained oral (without notations) for a long time until it also got its own notations.

The two leading scholars were fully recognized and promoted by the King for their accomplishments. They were given the title of azaze and homes were built for them near Tedbabe Mariam Church. While their contributions are quite significant, St Yared remains as the key composer of all the Zemas of the chants. He literally transformed the verses and texts of the Bible into musical utterances.

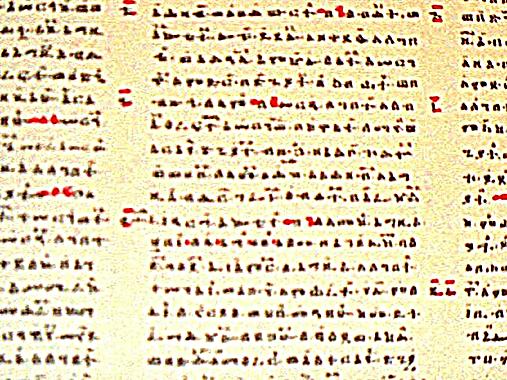

Figure 4. A sample page from St Yared’s zema or chant composition from Metsafe Digua Zeqidus Yared.

The ten chants are assigned names that fully described the range, scale and depth of Zema. Difat is a method of chanting where the voice is suppressed down in the throat and inhaling air. Hidet is a chant by stretching one’s voice; it is resembled to a major highway or a continuous water flow in a creek. Qinat is the highlighted last letter of a chant; it is chanted loud and upward in a dramatic manner and ends abruptly. Yizet is when letters or words are emphasized with louder chant in another wise regular reading form of chant. Qurt is a break from an extended chant that is achieved by withholding breathing. Chiret also highlights with louder notes letters or words in between regular readings of the text. The highlighted chant is conducted for a longer period of time. Rikrik is a layered and multiple chants conducted to prolong the chant. Diret is a form of chant that comes out of the chest. These eight chant forms have non-alphabetic signs. The remaining two are dirs and anber which are represented by Ethiopic or Ge’ez letters.

Yared’s composition also includes modes of chant and performance. There are four main modes. Qum Zema is exclusively vocal and the chant is not accompanied by body movement or swinging of the tau-cross staff. The chant is usually performed at the time of lent. Zimame chants are accompanied by body movements and choreographed swinging of the staff. Merged, which is further divided into Neus Merged and Abiy Merged are chanted accompanied by sistrum, drums, and shebsheba or sacred dance. The movements are fast, faster and fastest in merged, Neus Merged, and abiy merged respectively. Abiy Merged is further enhanced by rhythmic hand clappings. Tsifat chant highlights the drummers who move back and forth and around the Debteras. They also jump up and down, particularly with joyous occasions like Easter and Christmas.

St. Yared’s sacred music is truly classical, for it has been in use for over a thousand years and it has also established a tradition that continues to inform the spiritual and material lives of the people. It is in fact the realization of the contribution of St.Yared that earned him sainthood. Churches are built in his name and the first school of music that was established in the mid twentieth century in Addis Ababa is named after him. By the remarkable contribution of St. Yared, Ethiopia has achieved a tradition of modernity. It is the responsibility of the young generation to build upon it and to advance social, economic, and cultural development in the new millennium.

—–

Publisher’s Note: This article is well-referenced and those who seek the references should contact Professor Ayele Bekerie directly at: ab67@cornell.edu

About the Author:

Ayele Bekerie was born and raised in Ethiopia. He earned his Ph.D. in African American Studies at Temple University in 1994. He has written and published in scholarly journals, such as, Journal of Egyptology and African Civilizations (ANKH), Journal of Black Studies, The International Journal of Africana Studies, and Imhotep. He is also the author of Ethiopic: an African Writing System, a book about the history and principles of Ethiopic (Ge’ez). He is a Professor at Cornell University’s Africana Studies and Research Center. He is a regular contributor to Tadias Magazine.

—

Join the conversation on Twitter and Facebook

Born in 1941 Alemayehu Eshete rose to fame in the 60s, matching his Ethiopian heritage against jazz improvisation and soulful appeal...Multiple reports from Ethiopia have confirmed the passing of Alemayehu Eshete. (Getty Images)

Born in 1941 Alemayehu Eshete rose to fame in the 60s, matching his Ethiopian heritage against jazz improvisation and soulful appeal...Multiple reports from Ethiopia have confirmed the passing of Alemayehu Eshete. (Getty Images)