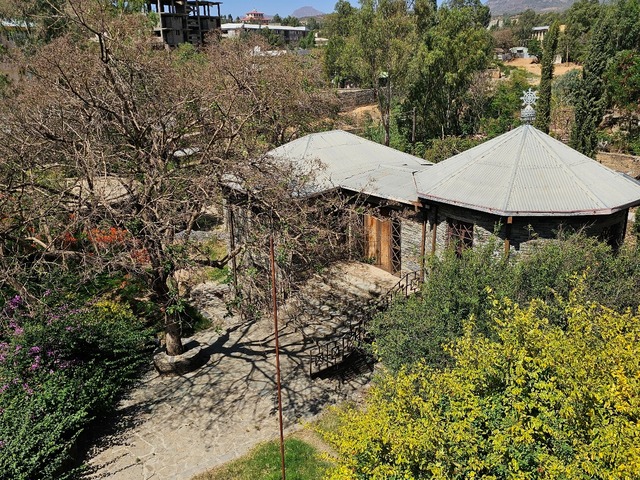

The historic Fasil Ghebbi in Gondar—an enduring symbol of Ethiopia’s architectural legacy and central to the life and work of architect Fasil Giorghis. (Photo courtesy of the author.)

The historic Fasil Ghebbi in Gondar—an enduring symbol of Ethiopia’s architectural legacy and central to the life and work of architect Fasil Giorghis. (Photo courtesy of the author.)

Tadias Magazine

Publisher’s Note:

In the following exclusive article, Alemayehu F. Weldemariam, Managing Editor of Africa Today, turns his focus to the quiet brilliance of Fasil Giorghis, one of Ethiopia’s most influential contemporary architects.

Through a richly textured narrative, Weldemariam offers readers a timely reflection on how Fasil’s life work blends restoration with civic purpose and architectural humility. From Gondar to sustainable public works in cities like Addis Ababa and Mekelle, Giorghis’s career is a testament to the belief that building is an act of remembering—and that true beauty listens more than it speaks.

We are honored to publish this timely contribution and invite you to explore this thoughtful tribute to a life spent in service of history, community, and design.

— Liben Eabisa, Publisher, Tadias Magazine

—

To Build Is to Remember: The Architecture of Fasil Giorghis

By Alemayehu Fentaw Weldemariam, Washington, D.C.

“Architecture should not dominate—it should listen.”

— Fasil Giorghis

Published: July 1st, 2025

TADIAS – Beauty, like truth or virtue, may belong to the domain of philosophy—but it migrates, insistently and unbidden, into art, poetry, music, and architecture. Plato himself spoke of the beauty of laws, constitutions, and institutions—order made humane, structure made just. Such is the pulse of my own doctoral work: seeking the convergence of beauty and justice in constitutional design.

Yet on this occasion, my attention turns to a different kind of architect—one who shapes not legal edifices but the lived environments of our cities. I recently attended a presentation by Fasil Giorghis, Ethiopia’s foremost architect, at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art. In his work, I saw a resplendent confluence of form and memory, stone and spirit. There was a profound lyricism in his use of light and material—a sense that architecture, like law, is ultimately about how we choose to inhabit the world together: what we preserve, what we enshrine, and what we dare to reimagine.

In a field too often dazzled by spectacle, the Ethiopian architect Fasil Giorghis has long preferred the quiet gesture. Whether restoring medieval churches, transforming imperial residences, or designing eco-toilets with local masons, his work is marked not by grandeur but by care. In a public conversation held on June 7, 2025 with Heran Sereke-Brhan, Deputy Director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art in Washington D.C., Giorghis offered a moving retrospective of a career rooted in memory, material knowledge, and moral purpose.

Growing Up in Gondar: A Young Architect in the Making

Born in Gondar, a city inscribed with the shadows of Ethiopia’s imperial past, Giorghis spent his early years weaving through historic courtyards, unknowingly absorbing the language of stone. After moving to Addis Ababa and completing his education at Teferi Mekonnen School, he joined the School of Architecture at Addis Ababa University. But instead of finding Ethiopia in the curriculum, he found only Europe. His dream was to be the Frank Lloyd Wright of Ethiopia.

The syllabus was rich in the history of western architecture but, poor in Lalibela and Gondar. Aksum’s geometric genius was nowhere to be found.

So he taught himself. With pen and brush in hand, he roamed the capital sketching neglected balconies, carved doorways, and worn colonnades—rendering them visible to a society already forgetting them.

Heritage as a Living Practice

If Giorghis is now recognized as one of the most eminent architects of Ethiopia, it is not for inventing a new style, but for reanimating an old ethos. His signature is not formal—it is ethical. Restoration, for him, is never about static preservation but about reuse with respect. He insists on adaptive transformations—reviving buildings not as fossils but as spaces for contemporary civic life.

This ethos stands in quiet dialogue with an earlier era of Ethiopian architectural ambition. In the 1960s, Addis Ababa underwent a dramatic construction boom, catalyzed by its rising international stature as host city to the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa and the newly founded Organization of African Unity. Under Emperor Haile Selassie, architecture became a diplomatic and symbolic instrument—an effort to materialize an African modernity that could stand alongside global peers yet remain anchored in Ethiopian tradition.

Working with expatriate architects like Arturo Mezzedimi, Henri Chomette, and the team of Zalman Enav and Michael Tedros, the imperial state sought to craft a built environment that fused international modernist vocabularies with local idioms. Italian colonial planning logics were reappropriated, not simply erased. The result was a distinctive imperial modernism—at once forward-looking and historically situated.

In this lineage, Giorghis’s work marks both a continuity and a corrective. Where Haile Selassie’s architects sculpted modernity through grand public works, Giorghis has channeled it through civic humility. The Red Terror Martyrs’ Memorial Museum, for example, was never conceived as a monumental gesture. Giorghis declined to build a triumphalist edifice and instead designed a quiet museum embedded into the slope of Meskel Square. Drawing on indigenous forms zigzagging masonry, rock-hewn transitions—the structure dignifies national memory without aestheticizing suffering.

The Red Terror Martyrs’ Memorial Museum in Addis Ababa. (Photo: courtesy of the author)

Top left: Axumite Heritage Foundation Library in Axum. Top right: Henock’s residence in Addis Ababa. Bottom left: Haile-Manas Academy in Debre Birhan and Ankober Lodge. (Photos courtesy of the author)

Similar humility animates his work on Addis’s urban heritage. The Alliance Éthio-Française was expanded with sensitive continuity. The Goethe-Institut, once the residence of Crown Prince Asfa Wossen, is now a thriving cultural center. These projects exemplify what Giorghis calls quiet activism—a form of architecture that does not shout but persuades.

“I am not an aggressive activist,” Giorghis says. “But I try to convince people—with reason, with example.”

The Team Behind the Vision

Giorghis is bold enough to deny the myth of the solitary genius. “This is not a one-man show,” he insists. “I work with brilliant, committed young Ethiopian architects.” Whether restoring Baata le Maryam Mausoleum, Takla Haimanot Church, the Taitu Cultural Center or the Trinity Cathedral in Addis Ababa, each project is a collaborative undertaking.

The Trinity Cathedral (Kidist Selassie) in Addis Ababa. Photo: courtesy of the author.

These restorations are supported by a remarkable array of benefactors—from government ministries to diaspora Ethiopians and working-class donors contributing a few coins. The architecture becomes communal.

“From very poor women to wealthy businessmen,” he observes, “people give what they can. That’s when you know it matters.”

Gondar: A City Reawakened

One of his most ambitious ongoing projects is the restoration of Gondar’s royal compound, including the 17th-century palace of Emperor Fasilides. The site, eroded by time and water, is being rehabilitated with original materials—lime, rock, and timber. But the effort goes far beyond stonework.

Giorghis and his team envision a socially integrated restoration: transforming the main palace into a museum, and surrounding buildings into workshops for local craftspeople—woodworkers, leather artisans, guides.

This model of preservation-as-livelihood is, in many ways, a microcosm of his architectural philosophy: buildings must serve both memory and economy.

Adwa: Stones of Memory and Paths of Renewal

Giorghis sees in the Adwa Heritage Preservation Project a rare and vital convergence: “a good example of public private partnership which involved the local community as well.” It is, in many ways, a model for how heritage work in Ethiopia—and indeed across Africa—might be reimagined. Rather than imposing preservation from above or outsourcing it to foreign benefactors, this initiative breathes from the ground up, rooted in the memory of place and animated by the stewardship of those who live among its fading stones.

Adwa Heritage Center. (Photo: courtesy of the author)

Initiated by Elizabeth Ambaye, a native daughter of Adwa, and her husband Rick Stoner, a former Peace Corps volunteer from Columbus, Indiana, the project is at once intimate and ambitious. What began as an effort to rebuild a single ancestral home has since evolved into a multi-pronged effort to rescue Adwa’s architectural past from erasure. The Adwa Heritage Center now stands completed—its walls enclosing not only a physical compound but a vision of cultural continuity. Adjacent to it, the Assem Park project restores the natural and urban landscape, offering safe pedestrian access and green reprieve in a city rapidly giving way to concrete ambitions. Most urgent of all is the Campaign to Save Old Adwa, a quiet rebellion against the logic of modernization that sees no value in what is old.

Here, Giorghis’s imprint is subtle but foundational. As professor and mentor, he has guided two graduate students in the painstaking task of mapping, photographing, and documenting the Medhane Alem neighborhood—one of Adwa’s oldest quarters and now officially designated as the city’s Old Town. This is not mere academic exercise. Their work, slated for exhibition at the Heritage Center, is a form of architectural witnessing: a visual and spatial record of what still stands, and what could yet be saved.

For Giorghis, this project embodies the principles he has long championed—architecture not as vanity, but as the quiet labor of memory. It is heritage preservation practiced with humility, in dialogue with place and people. That it emerged from a marriage of personal memory, public commitment, and pedagogical vision only confirms what he has long believed: that beauty, like justice, requires collaboration—and that the built environment, when treated with care, can become a vessel for both.

A Story from Lalibela

Heran Sereke-Brhan shared a telling anecdote during their public dialogue. One day in Lalibela, two casually dressed young men pulled Fasil aside. They had once been local tourist guides, she later learned, and had met a wealthy American couple who asked them their dreams. “To build a hotel,” they had said. The couple, moved, quietly financed the construction. Years later, that hotel—Mountain View—stands as a monument not to philanthropy, but to aspiration.

The original design was done by Sintayaehu, a young architect from Bahir Dar who was a student of Giorghis. For the second phase of the project, Giorghis became their consultant, guiding the structure’s latest expansion. Nearby, a young painter he once encouraged now runs a small gallery. These moments reveal his generosity of spirit—something he never mentions himself, but that others never forget.

Learning from the Vernacular

Giorghis has long championed vernacular architecture—not as an aesthetic, but as a knowledge system. In Aksum, he helped design a library using ancient construction techniques. In Mekelle, he designed dry, odorless ecological toilets using only earth and stone from the site—based on a model first tested in India, then indigenized for Tigray’s topography.

“When I go to a site,” he says, “the only outsider is me. Everything else is local.”

But these approaches are hard to scale. As one audience member asked, how does one build infrastructure for 70% of the population in rural areas using these methods?

“It’s very challenging,” Giorghis acknowledged. “There’s still resistance. When something is tied to tradition, it faces double the scrutiny.”

But through Ethiopia’s growing network of architectural schools, and with committed educators across the country, change is possible.

“We must prepare students not just to build, but to observe. Not just to draw, but to listen.”

The Architecture of Patience

His pedagogical ethos is best captured in a trip to Aksum in 1998. He brought 29 architecture students, who at first scoffed at the mud and rock houses. “What are we going to learn from this?” they asked. He said nothing. By the end of the week, they were transformed. “There is so much knowledge here,” they whispered. The humility had set in.

This is the architecture Fasil Giorghis teaches—and practices. One that attends to local material, to forgotten skill, to community voice. It is not the architecture of abstraction or ego. It is the architecture of relation—of reverence for place, and responsibility to people.

“Ethiopia has so much to offer—to the world, and to itself,” he says. “But to see it, you must be patient. You must find the middle point.”

In a world of rapidly vanishing places, Giorghis reminds us: to build is not just to create. It is to remember. To repair. To make space—for beauty, for justice, and for the slow dignity of time.

–

About the Author:

Alemayehu Fentaw Weldemariam is Managing Editor of Africa Today, published quarterly by Indiana University Press, and Orbis Africa, published by the Roy Sieber Chair in African Art History at Indiana University Bloomington and Diasporic Africa Press. He is a PhD Fellow at the Center for Constitutional Democracy, majoring in constitutional design and minoring in political philosophy.

Join the conversation on X and Facebook.