Henock Temesgen — bassist, composer, educator — reflects on four decades of shaping modern Ethiopian music from Addis Ababa to New York and back again. (Courtesy photo)

Henock Temesgen — bassist, composer, educator — reflects on four decades of shaping modern Ethiopian music from Addis Ababa to New York and back again. (Courtesy photo)

Tadias Magazine

By Alemayehu Fentaw Weldemariam

Published: July 25th, 2025

TADIAS Henock Temesgen is one of the foundational figures in contemporary Ethiopian music—a bassist, educator, and tireless collaborator whose career spans four decades and two continents. Born in Addis Ababa, he began his musical journey in church, was shaped by the Ibex Band’s trailblazing instrumental album, and came of age during the ferment of Ethiopia’s late 1970s music scene.

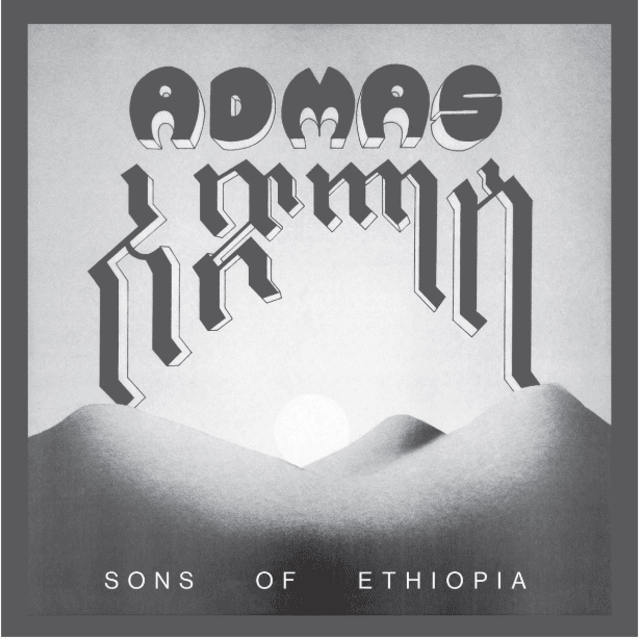

At 19, Henock moved to the United States on a student visa, initially studying civil engineering at George Mason and Howard University. But music was always calling. In 1984, alongside childhood friends Theodros Aklilu and Abegasu Shiota, he formed Admas, a Washington, D.C.-based band whose sole album, Sons of Ethiopia, fused jazz, funk, reggae, and Ethiopian modes into something entirely new. It became a cult classic and was reissued to critical acclaim in 2020.

Henock went on to earn dual degrees in Jazz Performance and Composition at Berklee College of Music. He became an established performer in New York City, playing with Ethiopian icons like Aster Aweke, Tilahun Gessesse, and Mahmoud Ahmed, while also backing major global acts at high-profile concerts from D.C. to Dubai.

Since returning to Addis Ababa in the early 2000s, Henock has co-founded the Jazzamba Music School and the African Jazz School, mentored a generation of rising musicians, and performed with top Addis-based ensembles like the Addis Acoustic Project and Nubian Ark. He hosts two radio shows on Sheger FM, curates his YouTube series Henock’s Practice Room, and continues to perform, teach, and record. A father of two, Henock balances a life of music with family, mentorship, and a quiet passion for architecture.

Interview

Alemayehu Weldemariam: Before we begin, I’d like to confirm that I have your consent to record and archive this conversation for reference and accuracy.

Henock Temesgen: Yes, you do. Thank you.

Alemayehu: To structure the conversation, I’d like to follow your journey chronologically—from your early musical beginnings in Addis Ababa to your years in the U.S., and your return to Ethiopia. Please feel free to reflect freely as we go.

Let’s start at the beginning. Where did your journey with the bass guitar begin? What drew you to that instrument?

Henock: When I was young, we lived in the Entoto area of Addis. We used to go to the Swedish mission, Mekane Yesus Church, on weekends. They had an organ and acoustic guitars, and we kids would mess around with them. I was about twelve. That was my first real exposure.

A friend named Barnabas taught us basic chords on guitar. I also figured out how to pick melodies on the organ. That’s when the spark really lit.

Later, when we moved to the Bole area, I met Abegasu Shiota. He had a piano at home. We’d jam together and eventually formed a school band called the Cavaliers.

Then, around 1978, we heard the Ibex Band’s instrumental album—with Giovanni Rico on bass, Dereje Mekonnen on keyboards, Selam Seyoum on guitar. That album changed everything for us. We learned all the tunes by ear and played along with the cassette. That’s when I really fell in love with the bass.

Alemayehu: So Giovanni was the formative influence?

Henock: Absolutely. Dereje and Selam were important too, but Giovanni’s bass lines stood out. They made me realize what the bass could do.

Diaspora Years and Musical Education

Alemayehu: How did you end up in the U.S.?

Henock: After finishing high school, my aunt—who had lived in the U.S. since Imperial times—sent me an I-20 from George Washington University. But tuition was too expensive, so I enrolled at George Mason University and later transferred to Howard University to complete a degree in civil engineering.

While at GWU, I met an Ethiopian woman who worked in the library. She asked where I went to school in Addis. I said St. Joseph’s. She said, “All my sons went there!” One of them was Theodros Aklilu—Teddy—who had been my classmate. She gave him my number, and a few months later he called me.

Teddy was playing keyboards in a band called Gasham in Washington, D.C. Their guitarist was Haile Ababa, and the bassist was American. Teddy told them about me, and I joined the group. We played at the Red Sea Restaurant.

Alemayehu: And this led to the formation of Admas?

Henock: Yes. In 1984, Abegasu came to the U.S. with Muluken Melesse. We reconnected, and along with Teddy, we started writing and recording in his basement. We laid down seven or eight tracks and pressed them on vinyl. That became Sons of Ethiopia by Admas. We printed 2,000 copies and sold about half.

The Sons of Ethiopia record by Admas band. (Courtesy photo)

After that, we went our separate ways. Teddy moved to Michigan. I worked as an engineer for three years while gigging on weekends. Then in 1990, I quit engineering and enrolled at Berklee College of Music in Boston. Abegasu joined me a year later. We both graduated in 1995 with double majors: Jazz Performance and Composition.

After Berklee, we moved to New York and became full-time musicians.

Return to Ethiopia and Teaching

Alemayehu: What brought you back to Ethiopia?

Henock: While living in New York, I performed regularly and toured with Ethiopian singers. Once a year, I’d fly to Addis to play at the Sheraton’s big holiday shows—opening for acts like Beyoncé and Rihanna.

During one of those trips, I gave workshops at the Yared Music School and Selam Music Academy. That’s when I discovered how much I loved teaching. After 9/11, the music scene in New York slowed, and the cost of living was rising. I was driving a limo three days a week to make rent.

Eventually, I decided to return to Addis. Teaching gave me a sense of purpose, and it felt like the right move.

Alemayehu: Do you still perform and record?

Henock: Yes, of course. I’ve been teaching for 18 years now, and many of my students are professional musicians. I also perform regularly with groups like Addis Acoustic Project, Nubian Ark, and the Village Band. I host two radio shows on Sheger FM and run a YouTube series called “Henock’s Practice Room”.

Musical Philosophy and the Bass Guitar

Alemayehu: When composing, what comes first—rhythm, melody, or mood?

Henock: Almost always melody. It’s like dressing a person—you start with the face. Then you build harmony, rhythm, color. I love jazz harmony, but I also use Ethiopian modes like Tizita, Bati, and Ambassel. It’s a fusion of my heritage and my training.

Alemayehu: What makes the bass such a compelling voice in Ethiopian music?

Henock: The bass is the glue. It connects the rhythm and the harmony. Most people don’t notice it, but it gives the music soul. I was heavily influenced by Motown players like James Jamerson. Bass is where I feel most at home.

Collaborations and Legacy

Alemayehu: Who have been your most meaningful collaborators?

Henock: Definitely Abegasu. Also Fasil Wuhib—we’ve worked together under AIT Records and still do. Jorga Mesfin, Samuel Yirga, Girum Mezmur, Teferi Assefa. I’ve also worked with international artists in Jazzmaris, Gojo Trio, and Nubian Ark.

Alemayehu: What performances stand out as especially meaningful?

Henock: There have been many—festivals in Europe, shows with Aster and Mahmoud. But the recent Admas reunion in Maryland was unforgettable. After 41 years, we were back on stage performing Sons of Ethiopia live. That was magical.

Alemayehu: What are you working on now?

Henock: We’re preparing to reissue Sons of Ethiopia again and sign with a label in Sweden. We’ll be touring in Europe. I continue to teach, perform, produce content, and raise my two sons. Life is full, and I’m grateful.

Beyond Music

Alemayehu: How would you like your work to be remembered?

Henock: As part of the continuum of Ethiopian music. As someone who tried to bring tradition and innovation together—and passed something meaningful on to the next generation.

Alemayehu: One final question—about your house. I heard Fasil Giorghis designed it, and you once said if you weren’t a musician, you’d have been an architect.

The Addis Ababa home of Henock Temesgen, thoughtfully designed by architect Fasil Giorghis to reflect the musician’s creative and architectural sensibilities. (Courtesy photo)

Henock: That’s true! I’ve always loved architecture. When I lived in New York, many of my friends lived in converted lofts—high ceilings, open plans, wood floors. When I had the chance to build a house in Addis, I knew I wanted that feel. Fasil helped bring it to life. Even now, I follow architecture closely. It’s still a passion.

Alemayehu: Thank you, Henock. You’ve been an extraordinary guest—thoughtful, generous, and inspiring.

Henock: Thank you. It’s been a pleasure.

–

About the Author:

Alemayehu Fentaw Weldemariam is Managing Editor of Africa Today, published quarterly by Indiana University Press, and Orbis Africa, published by the Roy Sieber Chair in African Art History at Indiana University Bloomington and Diasporic Africa Press. He is a PhD Fellow at the Center for Constitutional Democracy, majoring in constitutional design and minoring in political philosophy.

Related:

To Build Is to Remember: The Architecture of Fasil Giorghis in Ethiopia

Tadesse Mesfin and Ethiopian Modernism: Bridging Tradition and Innovation

Join the conversation on X and Facebook.