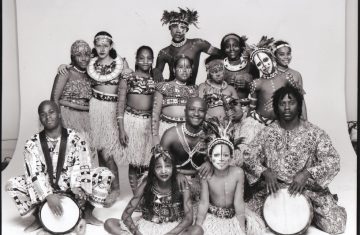

ABOVE: Members of Batoto Yetu, an African cultural children’s dance group based in New York. Julio Leitao is seated on center, second row.

BY GEORGE NELSON PRESTON

Batoto Yetu means “our children.”

Dancing in the Footsteps of Chibinda Ilunga

We recently had the opportunity to interview Julio Leitao, the internationally renown producer, choreographer, musicologist and consultant to governments on matters of traditional African culture.

In Swahili, the lingua franca of Eastern and much of Central Africa, batoto yetu means “our children.” In 1990 Julio Leitao, an Angolan born immigrant founded Batoto Yetu in East Harlem, New York City. Batoto Yetu is a children’s dance troupe dedicated to a cosmopolitan understanding in a post-ethnic world through the spreading of the African cultural heritage.

Preston: When did you arrive in the United States of America?

Julio Leitao: I came here from Lisbon the 7th of July, 1985 when I was 18 years old, in pursuit of a personal career in classical ballet. I studied at the Dance Theater of Harlem with Maggie Black. In 1989 I joined the Princeton Ballet.

Preston: How is it that you grew up in Portugal?

Julio Leitao: I arrived as a political refugee from Zambia in 1976 when I was 9 years old. My mother and seven brothers escaped the turmoil in Angola. We got separated from my father. We walked southerly all the way from the Kasai. We were living in a displaced person’s camp. We found out five years later that our father was dead. We were living in the Bush at Malba when we were finally rescued. From there we made our way to Portugal.

Preston: What was it like to grow up in Portugal, as an African Child from a country that had so recently won its independence through a long and bloody conflict with its former colonizer? I think I am correct to say that Portugal was the last European Colonial die-hard holdout in all of Africa.

Julio Leitao: When you are black and talented, you are perceived as special: artist, an athlete. I was a highly regarded soccer player and I embraced dance in a variety of forms from classical to folk. I had become a consistent media presence on a weekly basis. But this somehow made me more aware of my own racial reality.

Preston: You mean the dichotomy between the European’s response to the African in general and you in particular?

Julio Leitao: Yes. We Euro-Africans, born in Africa and having grown up in Europe. A people of convenience. Nowadays they’d prefer to give a job to an Eastern European.

Preston: Tell me some more about this reality that you awakened to, this paradox of identities. It seems to have been the catalyst that changed your pursuit of a personal career in dance to culture bearer to the Diaspora and beyond.

Julio Leitao: When I was sixteen years old, fate introduced me to Debbie Allen. She was in Portugal, a cultural emissary. Through my personal exposure to her during my dancing, choreographing and duties at the conservatory, I discovered the difference in how they treated her and me in their peculiar hierarchy of importance. They treated her like a goddess and I become nothing. The fact that this Black American could command so much respect made me think, I must go to New York to earn greater respect. This was during one of the major periods of intense fighting in Angola between UNITA and the MPLTA.

So by 1989 I was teaching classes for the National Black Theater in East Harlem. Then I started teaching children for free right there in the project playgrounds. I taught them dances such as mukanda from the Chokwe people’s boy’s initation rites, tshisela, another Luba dance, mutuashi, a Luba dance from the Kasai, and ndombolo, a pop dance, very commercial but great fun to watch. We did kapetula, an Angolan street culture dance and semba, from the Ovimbundu of Northwest Angola. Semba is the mother of samba. They also learned sabar from Senegal.

Preston: So we can say that Batoto Yetu was literally born of our children. What are you doing right now in addition to teaching dance and touring the U.S.A?

Julio Leitao: Since 1996 I worked with the Portuguese government to promote cultural awareness among the youth in Portugal. This is primarily a cultural service, but you can see the implications…its an important link with expanded social services as well. This is, mainly in Lisboa and Setubal.

Reflections

I mused on the cultural and family heritage of Julio. His mother’s first language was Kiluba, his father spoke Lingala, Kikongo, Portuguese, French, German and English. In the late 16th century Luba chieftains of the Ilunga dynasty began a campaign of exploration, discovery and conquest that was destined to create the cultural unification of what is now southeast DRC, northern and central Angola and west-central Zambia. Starting in eastern Lubaland , the Ilungas expanded their reach into the Katanga and Kasai of what is now the southern provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (ex Zaire). Around 1600 Chibinda Ilunga, a great Luba hunter-pathfinder met Lweji, a Lunda queen, and the Ilunga lineage expanded. The Chokwe in the north central of what is now Angola were then tributary to the Lunda. In the mid nineteenth century the Chokwe broke from the Lunda and the Chokwe culture including Chibunda, Ilunga’s revitalization of sacred kingship spread amongst the neighboring Mbundu, Lwena, Inbangala, Luchazi and Luvale peoples. Peoples, nearly all of whose homelands Julio and his family were to traverse on their way to sanctuary in Zambia.

For this writer, Julio’s birthplace, his long trek through the Kasai, Katanga and the terminus in Zambia followed greatly in the literal and cultural path of the Ilunga dynasty. He and his family had traversed much of the territory unified by the Ilungas. Now, here he was in New York City, teaching the dances of these very same peoples.

I thought of the uncommonly beautiful statues of the Chokwe and Lunda chiefs who trace their franchise to rule to the Ilungas. These statutes depict Chokwe chieftains in their royal hats and seated in postures of authority. Either seated and playing a thumb piano, or standing and holding medicine horns, rifles or walking staffs. Their outsized feet remind us of their great treks through forest and savanna.

Above: Generic Portrait of Chibinda Ilunga. These statues represent the present and pastChokwe chiefs all the way back to Chibinda Ilunga. Wood, H. 10.” Anonymous loan to the Museum of Art and Origins.

At age seven, Julio had found himself and the remnants of his family trekking along the footsteps of the Ilungas from Kasai, through Angola and finally to escape in Zambia. They had traversed the tribal territories of the Luba, Lunda, Kongo, Chokwe, Luchazi. Years later, in1989 Julio would introduce the dance steps of these peoples to the children of Africa, Europe and the Americas. All this makes me think of a phrase from the Baghavad Gita: The foot of the dance is everywhere in the whirling circumference.

O Ma God i love Julio he is the best .

keep doing your thing,

love enu

GREAT JULIO, thanks for your love and understanding to us all and the Portuguese too.You are typical angolan, full of tenderness, like in our popular verse: “puz a minha mao direita, na tua con afeicao,e vi como ela se ajeita ao jeito da minha mao”.( Julio will translate. ) This is difficult for americans to understand, as racism in colonial Portugal never reached the hights of anglo saxon (northern european) levels.

Beijinhos e abracos pro Julio,e as melhores felicidades.

Tua irma M. Leonor(failed portuguese danser of the white race)

I shall be in touch with Batoto Yetu when next in Lisbon, and hope to hear or meet you one day.