Marcus Samuelsson at his home in Harlem. The following is an excerpt from his book: 'Soul of A New Cuisine.' (Photo by Tesfaye Tessema for Tadias Magazine)

Marcus Samuelsson at his home in Harlem. The following is an excerpt from his book: 'Soul of A New Cuisine.' (Photo by Tesfaye Tessema for Tadias Magazine)

Tadias Magazine

By Marcus Samuelsson

Photos by Gideon Kifle

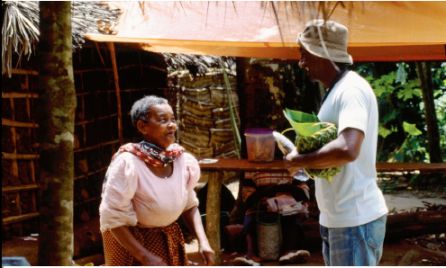

I WAS VISITING THE BAHAMA SPICE farm, a small, private farm where the faint, musky smell of cloves and cardamom danced on the breeze. Before me stretched a riotous tangle of greenery, sprouting spices I never imagined I’d have the opportunity to see growing—much less all in one place. As a chef, seeing how the spices I use daily are cultivated was like being in my own personal garden of Eden. It was an awe-inspiring afternoon I will never forget.

A guide walked me through the farm, challenging me to recognize the different spices that grew before us. Handing me a leaf from a large tree, he urged me to smell it to see if I could recognize the aroma. I sniffed and ventured a guess—“Cinnamon?”— and he smiled, happy to have stumped me. “No, it’s nutmeg,” he said, cracking open the mottled yellow fruit to reveal the tough brown kernel of nutmeg at its center.

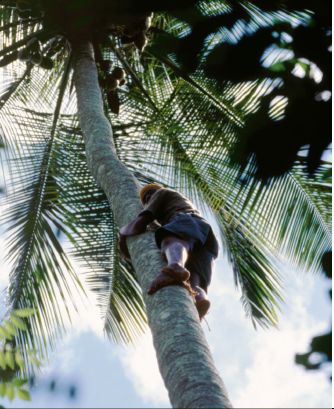

And so it went on our journey along the rambling path that ran through the spice patches. Before me, vanilla beans, ginger, cardamom, cloves, lemongrass, cocoa, cinnamon—all the magical flavors that inspire me every day—sprang from the ground, seemingly at random: a nutmeg tree here, a vanilla bean vine there, a cinnamon tree in the distance. We pulled ginger roots and lemongrass stalks from the ground, and watched our guide climb the branches of a tree to pluck a blossom that yielded tender, plump pink cloves, which would later be dried until they were shriveled and brown.

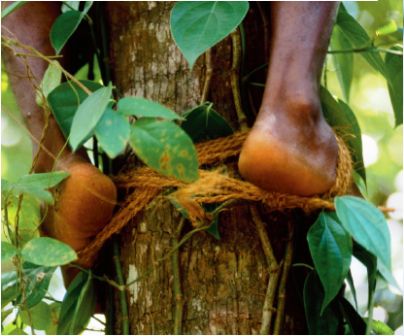

At the end of the tour, one of the boys accompanying us twisted a length of rope into a

a figure 8, hooked his feet into it, and used it to help him shimmy up the trunk of a tall, graceful coconut tree, disappearing into the sky to send a storm of coconuts raining down on us. Back on the ground, he cracked open a coconut and handed it to me. As I sipped the fresh, warm juice, I remembered hearing that long-ago sailors passing Zanzibar used to claim they could smell the scent of cloves drifting from the island far out to sea.

Today, Zanzibari farmers still eke out a living growing spices on small plots of land, but there was a time when spice plantations brought great riches to Zanzibar, a time whose legacy can still be seen in Stone Town, the faded but opulent heart of this vibrant island. Stone Town is one of the most magical cities I’ve ever visited. It’s a city of surprises—twisting narrow streets that seem to lead to nowhere, grand Arab palaces, Persian baths, mosques, temples, churches, hotels, restaurants, and shops, and sudden glimpses of the Indian Ocean framed between the crumbling stone buildings.

This magical, mysterious town is the place where the African, Arab, and Indian worlds meet. Hundreds of years ago, African fishermen, Arab and Persian traders, and Indian merchants all settled on the island. The Portuguese occupied Zanzibar beginning in 1503, but were forced out by the Omani Arabs in the late 1600s. Their defeat was followed by more than two hundred years of rule by Arab sultans.

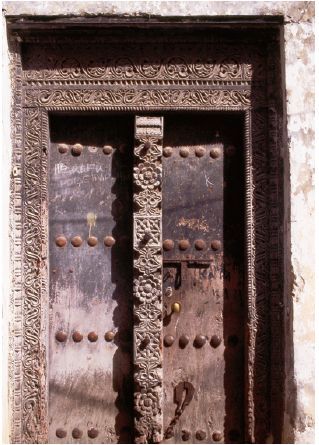

The sultans transformed Zanzibar, introducing cloves from Madagascar and building the first spice plantations. Thanks to the spice trade, the island quickly grew rich and the newly wealthy townspeople began rebuilding their mud homes with stone. The traditional Islamic modesty of these homes was accented with beautifully carved and studded doors, which are now one of the hallmarks of Stone Town. I was told these doors served a dual purpose—their ornate carving was a way for wealthy homeowners to show off their riches, while the studs were a symbol of protection for the inhabitants.

But, as in many of the places I visited in Africa, you can’t ignore history. All this grandeur has a dark side: at the height of the slave trade, as many as sixty thousand slaves a year were transported from the mainland to Zanzibar and sold to owners in Arabia, India, and French Indian Ocean possessions. I visited one of the prisons where the slaves were held—a cramped, dark, stark contrast to the stunning palaces built by the sultans who grew rich from the sale of slaves and spices.

During my brief visit, I drank in the sights, smells, and sounds of Zanzibar: fishermen sailing off in elegant dhows as the sun set over the Indian Ocean, the scent of grilled fish wafting from Stone Town’s nightly waterfront market at Forodhani Gardens, and the calling of the muezzin—the crier who summons the Muslim faithful to prayer five times a day from the mosque near our hotel. It’s a place of magic and mystique, whose very name conjures up a sense of enchantment and the smell of spices.

Recipe compliments of Marcus Samuelsson

C H I C K P E A – E G G P L A N T D I P

Hummus is now so ubiquitous that it’s hard to remember it was once an “exotic” food. It

was the first Moroccan food I ever had, and since that first bite I’ve grown to love the simplicity of Morocco’s many dips because they’re so easy to enjoy. You can serve this hummus-style dip on its own with warm pita wedges, as a spread on sandwiches, or as a distinctive accompaniment to grilled fish or chicken.

2 cups dried chickpeas, soaked in cold water for 8 hours

and drained

1 carrot, peeled and cut in half

1 medium Spanish onion, cut in half

4 garlic cloves, peeled

2 eggplants, cut lengthwise in half

4 cup plus 2 tablespoons olive oil

2 bird’s-eye chilies, cut in half, seeds and ribs removed

1 teaspoon Harissa (page 30)

1 teaspoon ground cumin

Combine the chickpeas, carrot, and onion in a medium saucepan, add 4 cups water, and bring to a boil. Reduce the heat and simmer until the chickpeas are very tender, about 11⁄2 hours. Drain, reserving 1 cup of the cooking liquid.

Meanwhile, preheat the oven to 300oF. Toss the garlic and eggplant with 1⁄4 cup of the olive oil and arrange on a roasting pan, eggplant cut side down. Roast for 40 minutes. Add the chilies to the roasting pan, cut side down, and roast for another 10 minutes. Set aside until cool enough to handle.

Scoop the flesh from the eggplant and transfer to a blender. Add the roasted garlic and chilies, chickpeas, harissa, cumin, the remaining 2 tablespoons oil, and 2 to 3 tablespoons of the reserved cooking liquid. Puree, adding more of the cooking liquid 2 to 3 tablespoons at a time as necessary, until the mixture is smooth and creamy. Serve at room temperature with warm Pita Bread (page 151).

MAKES 3 CUPS

You can purchase Marcus Samuelsson’s new book: Soul of A New Cuisine at Amazon.com

–

Join the conversation on Twitter and Facebook

I can’t forget the Bahamas Spice Farm because this farm caused me alot of trouble in my life when I lived in Zanzibar.