An international symposium entitled "Legacies of the Italian Occupation in Ethiopia" organized by Maaza Mengiste and Ruth Ben Ghiat will take place at NYU on October 24th, 2014. (Courtesy photos)

An international symposium entitled "Legacies of the Italian Occupation in Ethiopia" organized by Maaza Mengiste and Ruth Ben Ghiat will take place at NYU on October 24th, 2014. (Courtesy photos)

Tadias Magazine

Events News

Press Release: Primo Levi Center New York

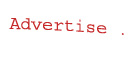

New York – This seminar focuses on the figure of Taamrat Emmanuel (1888 – 1963) a member of the Beta Israel Community in Ethiopia who, as a young man, was sent to study in France by the Polish Zionist and Orientalist Jacques Faitlovitch. Taamrat continued his education at the Collegio Rabbinico Italiano in Florence and went on to become a leader of Ethiopian Jewry as well as an Ethiopian leader during the dramatic years of the Italian occupation, World War II and the subsequent return to sovereign Ethiopia and the establishment of the State of Israel.

Emanuela Trevisan and Brook Abdu will explore Taamrat Emmanuel’s work and life through the documents he left in European and Ethiopian languages, concerning the occupation period and its aftermath.

Some historical and biographical information will help understand Taamrat’s connection with Italy and with the Italian Jewish establishment.

Italy’s colonial enterprise in East Africa started at the end of the 19th century with the takeover of Eritrea and Somalia. In 1935-36 from Eritrea, Italy invaded Ethiopia with a ruthless military aggression led by General Pietro Badoglio and later by Marshal Rodolfo Graziani. In spite of protest from the League of Nations, to which Ethiopia belonged, Italy imposed its rule over the country and remained in power until it lost it to the British in 1941.

Three groups of Jews lived in Ethiopia at the time: the Falasha, the Yemenites and the Adenites. Shortly after the invasion, The Union of the Italian Jewish Communities took interest in the situation of the local Jews, whose story had been known among Italian Jews since the early part of the century through a teacher of the Collegio Rabbinico in Florence, Taamrat Emmanuel and through Faitlovitch’s Committee for the Assistance of the Falasha. The UCII decided to send to Ethiopia Carlo Alberto Viterbo (1889-1974) with the purpose to “assist and organize the Jewish communities of ‘Africa Orientale Italiana’”. The UCII program included supporting the Jews of Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa and then expand assistance to the Jewish population residing on Lake Tana.

Carlo Alberto Viterbo was a lawyer from Florence, president of the first Italian Zionist Federation, a member of the Union of the Italian Jewish communities, a journalist and linguist.

In his eight months trip to Ethiopia (July 1936-March 1937), he entered local Jewish life and participated closely in the activities of the community both to create connections with Italy and to learn more abut the history, culture, languages and traditions of the Ethiopian Jews. During and after his journey, Viterbo prepared reports for the Union as well as for the Italian government, outlaying the development of vast and articulate study project on the history of the “Falasha”. Unfortunately, the project came to a halt soon after his return to Italy with the promulgation of the Racial Laws, in September 1938, and his subsequent arrest in June 1940.

After World War II Viterbo played a key role in the reconstruction of Jewish life and led the main Italian Jewish journal, Israel, from 1944 to 1974. He continued to develop his project on the study of the Ethiopian Jews that had by then shifted to a completely different geopolitical frame.

Taamrat Emmanuel and Jacques Faitlovitch

Taamrat Emmanuel (1888-1963) was born at Azazo near Gondar whose Jewish population, including his parents, had been converted to Christianity by missionaries.

He was thus raised as a convert or Falash Mura. Taamrat attended the School of the Sweedish Evangelical Mission in the Italian Eritrea. At age 16 he met the Polish Zionist Jacques Faitlovitch, who took him back with him to Paris to study at the Alliance Israélite Universelle. He continued his education at the Collegio Rabbinico Italiano in Florence under the guidance of Rabbi Samuel Hirsch Margulies and Tzvi Peretz-Hayot. Taamrat graduated as a rabbi and shochet and taught at the collegio until 1920.

In 1923, after spending almost two years in Palestine, Taamrat and Faitlovitch returned to Ethiopia where they established a Jewish school of which Taamrat became director. He undertook the translation of the Matzhaf Cadoussa (the scriptures of the Beta Israel community) from the Ge’ez language to the more widely used Amharic language.

Taamrat became one of the leaders of the Addis Ababa Jewish community. After the end of World War II Taamrat remained in Ethiopia and became a high ranking government representative in the field of education.

Jacques Faïtlovitch (1881-1955) was an orientalist, devoted to Beta Israel research and relief work. He was born in Lodz and studied Oriental languages at the École des Hautes Etudes in Paris, particularly Ethiopic and Amharic under Joseph Halévy, who interest him in the Beta Israel. Between 1904 and 1946 he traveled to Ethiopia 11 times. During his first trip he spent 18 months among the Beta Israel, studying their beliefs and customs. His research was published under the title Notes d’un voyage chez les Falachas (1905).

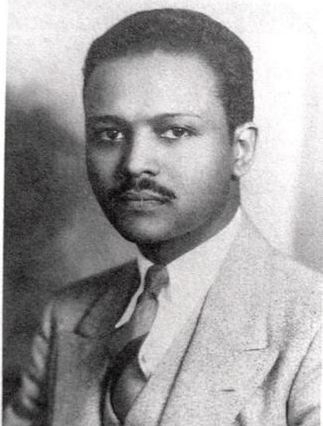

Convinced that Beta Israel needed help to resist Christian missionary activity, Faïtlovitch promised them to enlist world Jewry on their behalf and took two young Beta Israel with him to Europe to be educated as future teachers. Having failed to win the support of the Alliance Israélite Universelle, he organized “pro-Falasha” committees in Italy and Germany to raise funds for Jewish education in Abyssinia and abroad.

In 1913 he established one school in Dembea. After World War I transferred the center of pro-Falasha activity to the United States. In 1923, with the aid of the Joint Distribution Committee, he set up a boarding school for Beta Israel children in Addis Ababa.

Starting from 1927 Faïtlovitch settled in Tel Aviv but spent many years in the United States. The Italian conquest in 1935–36 hampered the expanding activity and World War II stopped it entirely. After the war he moved to Israel and resumed his work on behalf of the Beta Israel.

Taamrat Emmanuel: Between Colonizer and Colonized

Emanuela Trevisan (Università Ca’ Foscari, Venice)

Two different narratives have been consigned to history regarding the beginnings of European Jewry’s interest in the Jews of Ethiopia: those of Jacques Faitlovitch and Taamrat Emmanuel. The former is a success, the latter the opposite.

Faitlovitch, a self-confident Polish Jew, secure in his belief in the civilizing mission of the European Jews in the rebirth of the Ethiopian Jewish tradition, played a historical role in succeeding to forcefully bring to the attention of Western Jews the issue of Ethiopian Judaism.

Taamrat, the native from whom the adoption of Judaism in its European version was expected, as well as gratitude and total devotion to the “sacred cause”, ended up at the periphery of history, at the expense of his own life, his own feeling, his own ambitions and convictions.

Tamraat, who adopted the Italian language and accoutrements, who appears in photographs always elegant in a suit and tie, or bow tie, wholeheartedly adhered to European culture and Italian culture in particular, accepted most of the customs and traditions of European Jewry, but often found himself at odds with himself and had to struggle to get the respect of local traditions and the continuity of centuries old customs.

Taamrat, who served as a guide to Faitlovitch in Ethiopia, appears as a background figure, by no means one of the central characters in the story of the Beta Israel who left Ethiopia to immigrate to Israel, in the 1980’s.

The marginalization or disappearance of the protagonist, a native of the country, accompanying the European traveler, corresponds to a typology that occurs frequently in the history of the discoveries of the East and of the Jews of the East or of Africa of late nineteenth and twentieth century.

This presentation will try to show Taamrat’s different appartenance and identities, and, above all, the way he lived between two cultures, the Jewish-Italian and the Ethiopian.

In Italy he had the opportunity to encounter the Judaism of rabbi Margulies of Florence, as well as the assimilated Judaism and political values of that particularly eventful period in Italian history.

These were the years preceding the First World War, and the democratic and liberal principles expressed by great personalities such as Giuseppe Mazzini and Carlo Cattaneo, were perceived as a common patrimony.

These were also the years of socialism and personalities such as Raffaele Ottolenghi—a socialist close to Turati —treasurer of the pro-Falasha Committee, scholar of Judaism and of biblical prophets. Among others, Ottolenghi and the Italian anarchist Leda Rafanelli, whom Taamrat was tied to between 1917 to 1919, had a significant influence on him.

Throughout his story one seems to revisit the ambivalence mentioned by Albert Memmi about those Jews situated half way between colonizers and colonized, in that social reaction that kept the colonizer chained to the colonized, but in a more complex configuration, because it involves two types of Jews: the European Jew and the native Jew in a context such as the Ethiopian one, colonized both by the Jewish “counter mission” and the Italian occupation.

It is in this double identification with the Jewish, world as well as the Ethiopian world, that Taamrat Emmanuel’s personality was forged; it is this double identification that also defines his tormented path.

Taamrat Emmanuel in Post-Italian Ethiopia(1941-1948)

Brook Abdu (Research Fellow at the Capucin Franciscan Research and Retreat Center, Addis Ababa)

Recent research has shed much light on the lives of a group of Ethiopian Jews mentored by the famous Jewish missionary Jacques Faitlovitch (1881-1955). Especially, thanks to his extensive correspondence discovered in the Faitlovitch archives, the life of Taamrat Emmanuel (1888-1962) is now known in significant detail.

Brook Abdu will present new insights into the period previously least known in his life – the post-Italian invasion years of the 1940s. Using newly discovered sources (letters, newspaper articles and unpublished writings), he reconstructs Taamrat’s roles in the Ministry of Education (1941-1944), the Imperial Research Bureau (1944-1947) and the Eritrea Unity Association (1945-1948).

In the 1940s after slowly parting ways with his long-time mentor Faitlovitch, Taamrat found a new patron in the Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie (1892-1975) – a strong relationship that endured until the end of Taamrat’s life.

—

If You Go:

OCTOBER 23 | 4:00 PM – 7:00 PM

NYU Casa Italiana Zerilli Marimò

24 West 12th Street, NYC

LEGACIES OF THE ITALIAN OCCUPATION IN ETHIOPIA

OCTOBER 24, 2014 | 9:30 AM – 5:00 PM

NYU Casa Italiana Zerilli Marimò

9:30-10:00 Coffee and Welcome, Maaza Mengiste and Ruth Ben-Ghiat

10:00-11:30 Plays and Performance:

Heran Sereke-Brhan (Independent Researcher) in dialogue with Bewketu Seyoum (Independent Writer, Performer) Zerihun Birehanu (Addis Ababa University)

11:30-1:00 – Fiction:

Maaza Mengiste (New York University and Princeton University), in dialogue with Heran Sereke-Brhan (Independent Researcher) and Dagmawi Woubshet (Cornell University)

1:00-2:30 – Lunch

2:30-4:00 – Visual Arts:

Ruth Ben-Ghiat (New York University) in dialogue with Abiyi Ford (Addis Ababa University) and Shiferaw Bekele (Addis Ababa University). Screening of clips from Da Adwa ad Axum/From Adwa to Axum (Luce, 1936), and Adwa (Haile Gerima, 1999).

4:00 Closing Remarks by Abiyi Ford and Discussion with the Audience

—

More info at Primo Levi Center New York

Join the conversation on Twitter and Facebook.