Former U.S. President Barack Obama is the first American leader to visit Ethiopia while in office. (Photo by Pete Souza / The White House)

Former U.S. President Barack Obama is the first American leader to visit Ethiopia while in office. (Photo by Pete Souza / The White House)

Tadias Magazine

June 7th, 2020

Publisher/Editor’s note: Over the years Tadias has featured several original stories highlighting the long history of people to people relations between African Americans and Ethiopians dating back more than 200 years and covering literature, art history and politics. The latter aside, this friendship culminated when former U.S. President Barack Obama, America’s first Black president, became the only sitting U.S. president to visit Ethiopia and address the African Union from its headquarters in Addis Ababa five years ago this summer. In light of current events and in solidarity with the growing Black Lives Matter protest in the United States we are republishing these articles to spotlight the timeless and enduring cross-cultural relationships that were often forged under difficult historical circumstances.

Harlem: African American and Ethiopian Relations

Jazz great Duke Ellington toasts with Emperor Haile Selassie after receiving Ethiopia’s Medal of Honor in 1973. (Photo: Ethiopiancrown.org)

Tadias Magazine

By Tseday Alehegn

August 2008

New York (TADIAS) – Ethiopia stands as the oldest, continuous, black civilization on earth, and the second oldest civilization in history after China. This home of mine has been immortalized in fables, legends, and epics. Homer’s Illiad, Aristotle’s A Treatise on Government, Miguel Cervante’s Don Quixote, the Bible, the Koran, and the Torah are but a few potent examples of Ethiopia’s popularity in literature. But it is in studying the historical relations between African Americans and Ethiopians that I came to understand ‘ Ethiopia’ as a ray of light. Like the sun, Ethiopia has spread its beams on black nations across the globe. Her history is carefully preserved in dust-ridden books, in library corners and research centers. Her beauty is caught by a photographer’s discerning eye, her spirituality revived by priests and preachers. Ultimately, however, it is the oral journals of our elders that helped me capture glitters of wisdom that would palliate my thirst for a panoptic and definitive knowledge.

The term ‘Ethiopian’ has been used in a myriad of ways; it is attributed to the indigenous inhabitants of the land located in the Eastern Horn of Africa, as well as more generally denotive of individuals of African descent. Indeed, at one time, the body of water now known as the Atlantic Ocean was known as the Ethiopian Ocean. And it was across this very ocean that the ancestors of African Americans were brought to America and the ‘ New World.’

Early African American Writers

Although physically separated from their ancestral homeland and amidst the opprobrious shackles of slavery, African American poets, writers, abolitionists, and politicians persisted in forging a collective identity, seeking to link themselves figuratively if not literally to the African continent. One of the first published African American writers, Phillis Wheatly, sought refuge in referring to herself as an “Ethiop”. Wheatley, an outspoken poet, was also one of the earliest voices of the anti-slavery movement, and often wrote to newspapers of her passion for freedom. She eloquently asserted, “In every human breast God has implanted a principle, it is impatient of oppression.” In 1834 another anti-slavery poet, William Stanley Roscoe, published his poem “The Ethiop” recounting the tale of an African fighter ending the reign of slavery in the Caribbean. Paul Dunbar’s notable “Ode to Ethiopia,” published in 1896, was eventually put to music by William Grant Still and performed in 1930 by the Afro-American Symphony. In his fiery anti-slavery speech entitled “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” prominent black leader Frederick Douglas blazed at his opponents, “Africa must rise and put on her yet unwoven garment. Ethiopia shall stretch out her hand unto God.”

First Ethiopians Travel to America

As African Americans fixed their gaze on Ethiopia, Ethiopians also traveled to the ‘New World’ and learned of the African presence in the Americas. In 1808 merchants from Ethiopia arrived at New York’s famous Wall Street. While attempting to attend church services at the First Baptist Church of New York, the Ethiopian merchants, along with their African American colleagues, experienced the ongoing routine of racial discrimination. As an act of defiance against segregation in a house of worship, African Americans and Ethiopians organized their own church on Worth Street in Lower Manhattan and named it Abyssinia Baptist Church. Adam Clayton Powell, Sr. served as the first preacher, and new building was later purchased on Waverly Place in the West Village before the church was moved to its current location in Harlem. Scholar Fikru Negash Gebrekidan likewise notes that, along with such literal acts of rebellion, anti slavery leaders Robert Alexander Young and David Walker published pamphlets entitled Ethiopian Manifesto and Appeal in 1829 in an effort to galvanize blacks to rise against their slave masters.

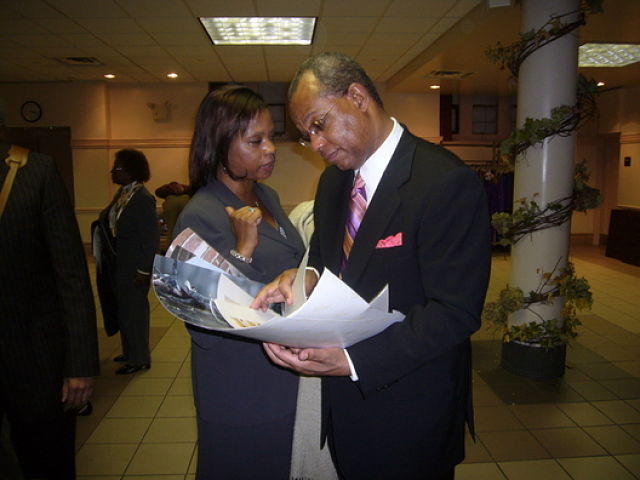

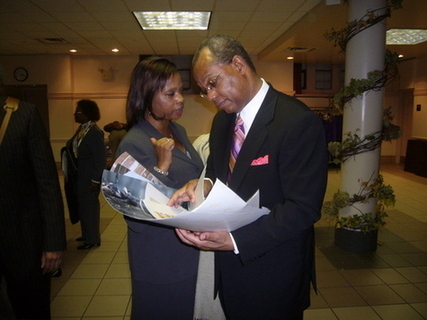

Reverend Dr. Calvin O. Butts, III, current head of the Abyssinia Baptist Church in Harlem, led a delegation of 150 to Ethiopia in 2007 as part of the church’s bicentennial celebration. (Photo: At Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, New York on Sunday, November 4, 2007/Tadias)

Adwa Victory & ‘Back to Africa’ Movement

When Italian colonialists encroached on Ethiopian territory and were soundly defeated in the Battle of Adwa on March 1, 1896, it became the first African victory over a European colonial power, and the victory resounded loud and clear among compatriots of the black diaspora. “For the oppressed masses Adwa…would become a cause célèbre,” writes Gebrekidan, “a metaphor for racial pride and anti-colonial defiance, living proof that skin color or hair texture bore no significance on intellect and character.” Soon, African Americans and blacks from the Caribbean Islands began to make their way to Ethiopia. In 1903, accompanied by Haitian poet and traveler Benito Sylvain, an affluent African American business magnate by the name of William Henry Ellis arrived in Ethiopia to greet and make acquaintances with Emperor Menelik. A prominent physician from the West Indies, Dr. Joseph Vitalien, also journeyed to Ethiopia and eventually became Menelik’s trusted personal physician.

For black America, the early 1900s was a time consumed with the notion of “returning to Africa,” to the source. With physical proof of the beginnings of colonial demise, a charismatic and savvy Jamaican immigrant and businessman named Marcus Garvey established his grassroots organization in 1917 under the title United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) with branches in various states. Using the success of Ethiopia’s independence as a beacon of freedom for blacks residing in the Americas, Garvey envisioned a shipping business that would raise enough money and register members to volunteer to be repatriated to Africa. In a few years time, Garvey’s UNIA raised approximately ten million dollars and boasted an impressive membership of half a million individuals.

Notable civil rights leader Malcolm X began his autobiography by mentioning his father, Reverend Earl Little, as a staunch supporter of the UNIA. “It was only me that he sometimes took with him to the Garvey U.N.I.A. meetings which he held quietly in different people’s homes,” says Malcolm. “I can remember hearing of ‘ Africa for the Africans,’ ‘Ethiopians, Awake!’” Malcolm’s early association with Garvey’s pan-African message resonated with him as he schooled himself in reading, writing, and history. “I can remember accurately the very first set of books that really impressed me,” Malcolm professes, “J.A. Rogers’ three volumes told about Aesop being a black man who told fables; about the great Coptic Christian Empires; about Ethiopia, the earth’s oldest continuous black civilization.”

By the time the Ethiopian government had decided to send its first official diplomatic mission to the United States in 1919, Marcus Garvey had already emblazoned an image of Ethiopia into the minds and hearts of his African American supporters. “I see a great ray of light and the bursting of a mighty political cloud which will bring you complete freedom,” he promised them, and they in turn eagerly propagated his message.

The Harlem Renaissance & Emigrating to Ethiopia

A headline by the Chicago Defender announcing the arrival of the first Ethiopian diplomatic delegation to the United States on July 11, 1919.

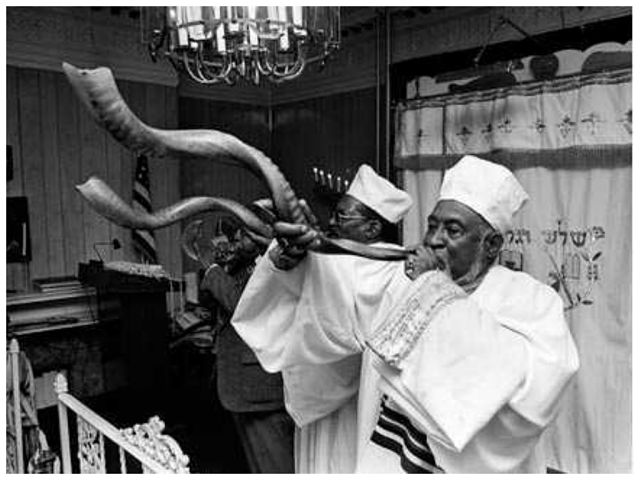

In 1919 an official Ethiopian goodwill mission was sent to the United States, the first African delegation of diplomats, in hopes of creating amicable ties with the American people and government. The four-person delegation included Dejazmach Nadew, Ato Belanteghetta Hiruy Wolde Selassie, Kentiba Gebru, and Ato Sinkas. Having been acquainted with African Americans such as businessman William Ellis, Kentiba Gebru, the mayor of Gondar, made a formal appeal during his trip for African Americans to emigrate to Ethiopia. Arnold Josiah Ford, a Harlem resident from Barbados, had an opportunity to meet the 1919 Ethiopian delegation. Having already heard of the existence of black Jews in Ethiopia, Ford established his own synagogue for the black community soon after meeting the Ethiopian delegation. Along with a Nigerian-born bishop named Arthur Wentworth Matthews, Ford created the Commandment Keepers Church on 123rd Street in Harlem and taught the congregation about the existence of black Jews in Ethiopia. Meanwhile, in the international spotlight, 1919 was the year the League of Nations was created, of which Ethiopia became the first member from the African continent. The mid 1900s gave birth to the Harlem Renaissance. With many African Americans migrating to the north in search of a segregation-free life, and a large contention of black writers, actors, artists and singers gathering in places like Harlem, a new culture of black artistic expression thrived. Even so, the Harlem Renaissance was more than just a time of literary discussions and hot jazz; it represented a confluence of creativity summoning forth the humanity and pride of blacks in America – a counterculture subverting the grain of thought ‘separate and unequal.’

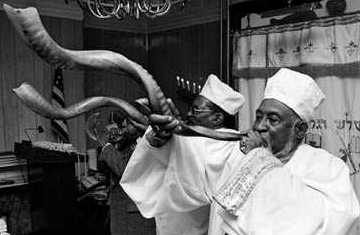

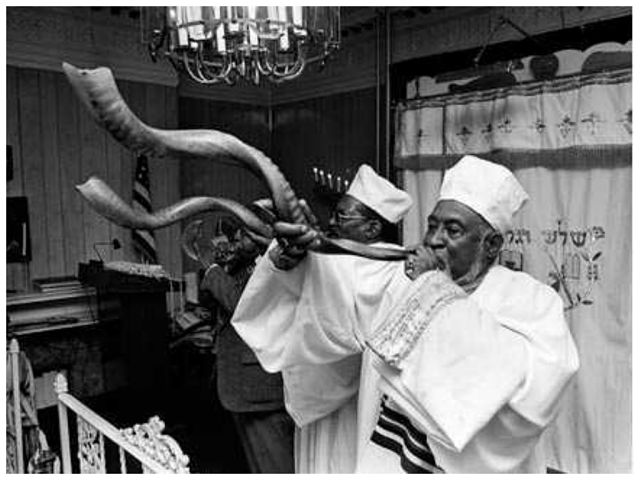

Commandment Keepers Synagogue. (Photography by Chester Higgins. ©chesterhiggins.com)

As in earlier times, the terms ‘Ethiopian’ and ‘Ethiop’ continued to be utilized by Harlem writers and poets to instill black pride. In other U.S. cities like Chicago, actors calling themselves the ‘National Ethiopian Art Players’ performed The Chip Woman’s Fortune by Willis Richardson, the first serious play by a black writer to hit Broadway.

In 1927, Ethiopia’s Ambassador to London, Azaj Workneh Martin, arrived in New York and appealed once again for African American professionals to emigrate and work in Ethiopia. In return they were promised free land and high wages. In 1931 the Emperor granted eight hundred acres for settlement by African Americans, and Arnold Josiah Ford, bishop of the Commandment Keepers Church, became one of the first to accept the invitation. Along with sixty-six other individuals, Ford emigrated and started life anew in Ethiopia.

Ethiopian Students in America: Mobilizing Support

In November 1930, Haile Selassie was coronated as Emperor of Ethiopia. The event blared on radios, and Harlemites heard and marveled at the ceremonies of an African king. The emperor’s face glossed the cover of Time Magazine, which remarked on black news outlets in America hailing the king “as their own.” African American pilot Hubert Julian, dubbed “The Black Eagle of Harlem,” had visited Ethiopia and attended the coronation. Describing the momentous occasion to Time Magazine, Hubert rhapsodized:

“When I arrived in Ethiopia the King was glad to see me… I took off with a French pilot… We climbed to 5,000 ft. as 50,000 people cheered, and then I jumped out and tugged open my parachute… I floated down to within 40 ft. of the King, who incidentally is the greatest of all modern rulers… He rushed up and pinned the highest medal given in that country on my breast, made me a colonel and the leader of his air force — and here I am!”

Joel Augustus Rogers, famed author and correspondent for New York’s black newspaper Amsterdam News, also covered the Coronation of Haile Selassie and was likewise presented with a coronation medal.

After his official coronation, Emperor Haile Selassie sent forth the first wave of Ethiopian students to continue their education abroad. Melaku Beyan was a member of the primary batch of students sent to America in the 1930s. He attended Ohio State University and later received his medical degree at Howard Medical School in Washington, D.C. During his schooling years at Howard, he forged lasting friendships with members of the black community and, at Emperor Haile Selassie’s request, he endeavored to enlist African American professionals to work in Ethiopia. Beyan was successful in recruiting several individuals, including teachers Joseph Hall and William Jackson, as well as physicians Dr. John West and Dr. Reuben S. Young, the latter of whom began a private practice in Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, prior to his official assignment as a municipal health officer in Dire Dawa.

African American professionals in Addis Ababa – 1942: Kneeling, left to right, Andrew Howard Hester, Edward Eugene Jones, Edgar E. Love. Standing, left to right, David Talbot, Thurlow Evan Tibbs, James William Cheeks, the Reverend Mr. Hamilton, John Robinson, Edgar D. Draper (Photo: Crown Council of Ethiopia)

Italo-Ethiopian War 1935-1941

Melaku Beyan

By the mid 1930s the Emperor had sent a second diplomatic mission to the U.S. Vexed at Italy’s consistently aggressive behavior towards his nation, Haile Selassie attempted to forge stronger ties with America. Despite being a member of the League of Nations, Italy disregarded international law and invaded Ethiopia in 1935. The Ethiopian government appealed for support at the League of Nations and elsewhere, through representatives such as the young, charismatic speaker Melaku Beyan in the United States. Beyan had married an African American activist, Dorothy Hadley, and together they created a newspaper called Voice of Ethiopia to simultaneously denounce Jim Crow in America and fascist invasion in Ethiopia. Joel Rogers, the correspondent who had previously attended the Emperor’s coronation, returned to Ethiopia as a war correspondent for The Pittsburgh Courier, then America’s most widely-circulated black newspaper. Upon returning to the United States a year later, he published a pamphlet entitled The Real Facts About Ethiopia, a scathing and uncompromising report on the destruction caused by Italian troops in Ethiopia. Melaku Beyan used the pamphlet in his speaking tours, while his wife Dorothy designed and passed out pins that read “Save Ethiopia.”

In Harlem, Chicago, and various other cities African American churches urged their members to speak out against the invasion. Beyan established at least 28 branches of the newly-formed Ethiopian World Federation, an organ of resistance calling on Ethiopians and friends of Ethiopia throughout the United States, Europe, and the Caribbean. News of Ethiopia’s plight fueled indignation and furious debates among African Americans. Touched by the Emperor’s speech at the League of Nations, Roger’s accounts, and Melaku’s impassioned message, blacks vowed to support Ethiopia. Still others wrote letters to Haile Selassie, some giving advice, others support and commentary. “I pray that you will deliver yourself from crucifixion,” wrote one black woman from Los Angeles, “and show the whites that they are not as civilized as they loudly assert themselves to be.”

Although the United States was not officially in support of Ethiopia, scores of African Americans attempted to enlist to fight in Ethiopia. Unable to legally succeed on this front, several individuals traveled to Ethiopia on ‘humanitarian’ grounds. Author Gail Lumet Buckley cites two African American pilots, John Robinson and the ‘Black Eagle of Harlem’ Hubert Julian, who joined the Ethiopian Air Force, then made up of only three non-combat planes. John Robinson, a member of the first group of black students that entered Curtis Wright Flight School, flew his plane delivering medical supplies to different towns across the country. Blacks in America continued to stand behind the Emperor and organized medical supply drives from New York’s Harlem Hospital. Melaku Beyan and his African American counterparts remained undeterred for the remainder of Ethiopia’s struggle against fascism. In 1940, a year before Ethiopia’s victory against Italy, Melaku Beyan succumbed to pneumonia, which he had caught while walking door-to-door in the peak of winter, speaking boldly about the war for freedom in Ethiopia.

Above: Colonel John C. Robinson arrives in Chicago after heroically

leading the Ethiopian Air Force against the invading Mussolini’s

Italian forces. (Photo via Ethiopiancrown.org)

Lasting Legacies: Ties That Bind

Traveling through Harlem in my mind’s eye, I see the mighty organs of resistance that played such a pivotal role in “keeping aloft” the banner of Ethiopia and fostering deep friendships among blacks in Africa and America. I envision the doors Melaku Beyan knocked on as he passed out pamphlets; the pulpits on street corners where Malcolm X stood preaching about the strength and beauty of black people, fired up by the history he read. The Abyssinia Baptist Church stands today bigger and bolder, and inside you find the most exquisite Ethiopian cross, a gift from the late Emperor Haile Selassie to the people of Harlem and a symbol of love and gratitude for their support and friendship.

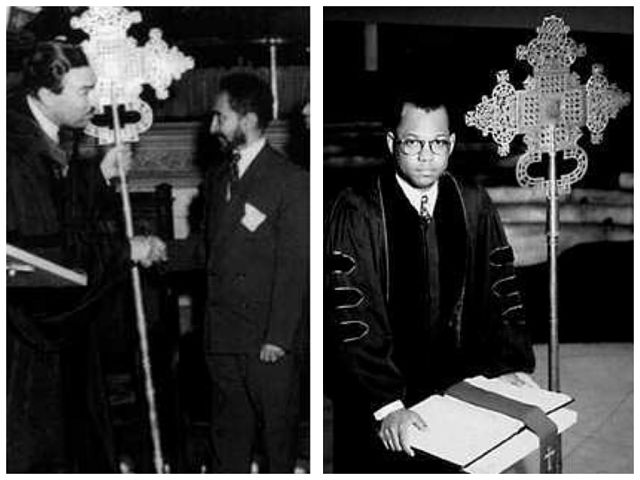

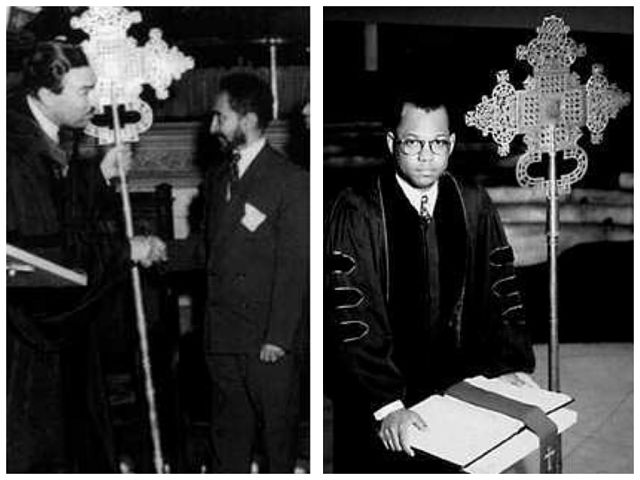

Left, Emperor Haile Selassie presenting the cross to Reverend Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., on May 27, 1954. (Photography by Marvin Smith). Right, Rev. Dr. Calvin Butts, the current head of the Abyssinia Baptist Church.

Several Coptic churches line the streets of Harlem, and the ancient synagogue of the Commandment Keepers established by Arnold Ford continues to have Sabbath services. The offices of the Amsterdam News are still as busy as ever, recording and recounting the past and present state of black struggles. Over the years, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture has carefully preserved the photographic proofs of the ties that bind African Americans and Ethiopians, just in case the stories told are too magical to grasp.The name ‘Ethiopia’ conjures a kaleidoscope of images and verbs. In researching the historical relations between African Americans and Ethiopians, I learned that Ethiopia is synonymous with ‘freedom,’ ‘black dignity’ and ‘self-worth.’ In the process, I looked to my elders and heeded the wisdom they have to share. In his message to the grassroots of Detroit, Michigan, Malcolm X once asserted, “Of all our studies, history is best qualified to reward our research.” It is this kernel of truth that propelled me to share this rich history in celebration of Black History Month and the victory of Adwa.

In attempting to understand what Ethiopia really means, I turn to Ethiopia’s Poet Laureate Tsegaye Gabre-Medhin. “The Ethiopia of rich history is the heart of Africa’s civilization,” he said. “She is the greatest example of Africa’s pride. Ethiopia means peace. The word ‘ Ethiopia’ emanates from a connection of three old Egyptian words, Et, Op and Bia, meaning truth and peace, up and upper, country and land. Et-Op-Bia is land of upper truth or land of higher peace.”

Poet Laureate Tsegaye Gebremedhin reading an article about him on the 10th issue of Tadias Magazine, which was dedicated to African American & Ethiopia Relations. (Photo © Chester Higgins, Jr.)

This is my all-time, favorite definition of Ethiopia, because it brings us back to our indigenous roots: The same roots that African Americans and the diaspora have searched for; the same roots from which we have sprung and grown into individuals rich in confidence. Welcome to blackness. Welcome to Ethiopia!

—

The Case of Melaku E. Bayen and John Robinson: Ethiopia, America and the Pan-African Movement

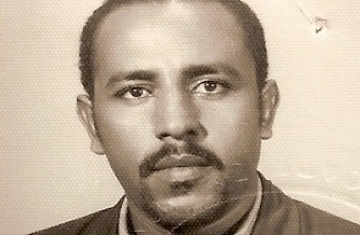

Photo: Melaku E. Beyan. (Wikimedia)

Tadias Magazine

By Ayele Bekerie, PhD

Updated: April 18th, 2007

New York (TADIAS) — Seventy two years ago, African Americans of all classes, regions, genders, and beliefs expressed their opposition to and outrage over the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in various forms and various means. The invasion aroused African Americans – from intellectuals to common people in the street – more than any other Pan-African-oriented historical events or movements had. It fired the imagination of African Americans and brought to the surface the organic link to their ancestral land and peoples.

1935 was indeed a turning point in the relations between Ethiopia and the African Diaspora. Harris calls 1935 a watershed in the history of African peoples. It was a year when the relations substantively shifted from symbolic to actual interactions. The massive expression of support for the Ethiopian cause by African Americans has also contributed, in my opinion, to the re-Africanization of Ethiopia. This article attempts to examine the history of the relations between Ethiopians and African Americans by focusing on brief biographies of two great leaders, one from Ethiopia and another one from African America, who made extraordinary contributions to these relations.

It is fair to argue that the Italo-Ethiopian War in the 1930s was instrumental in the rebirth of the Pan-African movement. The African Diaspora was mobilized in support of the Ethiopian cause during both the war and the subsequent Italian occupation of Ethiopia. Italy’s brutal attempt to wipe out the symbol of freedom and hope to the African world ultimately became a powerful catalyst in the struggle against colonialism and oppression. The Italo-Ethiopian War brought about an extraordinary unification of African people’s political awareness and heightened level of political consciousness. Africans, African Americans, Afro-Caribbean’s, and other Diaspora and continental Africans from every social stratum were in union in their support of Ethiopia, bringing the establishment of “global Pan-Africanism.” The brutal aggression against Ethiopia made it clear to African people in the United States that the Europeans’ intent and purpose was to conquer, dominate, and exploit all African people. Mussolini’s disregard and outright contempt for the sovereignty of Ethiopia angered and reawakened the African world.

Response went beyond mere condemnation by demanding self-determination and independence for all colonized African people throughout the world. For instance, the 1900-1945 Pan-African Congresses regularly issued statements that emphasized a sense of solidarity with Haiti, Ethiopia, and Liberia, thereby affirming the importance of defending the sovereignty and independence of African and Afro-Caribbean states. A new generation of militant Pan-Africanists emerged who called for decolonization, elimination of racial discrimination in the United States, African unity, and political empowerment of African people.

One of the most significant Pan-Africanist Conferences took place in 1945, immediately after the defeat of the Italians in Ethiopia and the end of World War II. This conference passed resolutions clearly demanding the end of colonization in Africa, and the question of self-determination emerged as the most important issue of the time. As Mazrui and Tidy put it: “To a considerable extent the 1945 Congress was a natural outgrowth of Pan-African activity in Britain since the outbreak of the Italo-Ethiopian War.”

Another of the most remarkable outcomes of the reawakening of the African Diaspora was the emergence of so many outstanding leaders, among them the Ethiopian Melaku E. Bayen and the African American John Robinson. Other outstanding leaders were Willis N. Huggins, Arnold Josiah Ford, and Mignon Innis Ford, who were active against the war in both the United States and Ethiopia. Mignon Ford, the founder of Princess Zenebe Work School, did not even leave Ethiopia during the war. The Fords and other followers of Marcus Garvey settled in Ethiopia in the 1920s. Mignon Ford raised her family among Ethiopians as Ethiopians. Her children, fluent speakers of Amharic, have been at home both in Ethiopia and the United States.

Pan-Africanists in Thoughts & Practice

Melaku E. Bayen, an Ethiopian, significantly contributed to the re-Africanization of Ethiopia. His noble dedication to the Pan-African cause and his activities in the United States helped to dispel the notion of “racial fog” that surrounded the Ethiopians. William R. Scott expounded on this: “Melaku Bayen was the first Ethiopian seriously and steadfastly to commit himself to achieving spiritual and physical bonds of fellowship between his people and peoples of African descent in the Americas. Melaku exerted himself to the fullest in attempting to bring about some kind of formal and continuing relationship designed to benefit both the Ethiopian and Afro-American.” To Scott, Bayen’s activities stand out as “the most prominent example of Ethiopian identification with African Americans and seriously challenges the multitude of claims which have been made now for a long time about the negative nature of Ethiopian attitudes toward African Americans.”

The issues raised by Scott and the exemplary Pan-Africanism of Melaku Bayen are useful in establishing respectful and meaningful relations between Ethiopia and the African Diaspora. They dedicated their entire lives in order to lay down the foundation for relations rooted in mutual understanding and historical facts, free of stereotypes and false perceptions. African American scholars, such as William Scott, Joseph E. Harris, and Leo Hansberry contributed immensely by documenting the thoughts and activities of Bayen, both in Ethiopia and the United States.

Melaku E. Bayen was raised and educated in the compound of Ras Mekonnen, then the Governor of Harar and the father of Emperor Haile Selassie. He was sent to India to study medicine in 1920 at the age of 21 with permission from Emperor Haile Selassie. Saddened by the untimely death of a young Ethiopian woman friend, who was also studying in India, he decided to leave India and continue his studies in the United States. In 1922, he enrolled at Marietta College, where he obtained his bachelor’s degree. He is believed to be the first Ethiopian to receive a college degree from the United Sates.

Melaku started his medical studies at Ohio State University in 1928, then, a year later, decided to transfer to Howard University in Washington D.C. in order to be close to Ethiopians who lived there. Melaku formally annulled his engagement to a daughter of the Ethiopian Foreign Minister and later married Dorothy Hadley, an African American and a great activist in her own right for the Ethiopian and pan-Africanist causes. Both in his married and intellectual life, Melaku wanted to create a new bond between Ethiopia and the African Diaspora.

Melaku obtained his medical degree from Howard University in 1936, at the height of the Italo-Ethiopian War. He immediately returned to Ethiopia with his wife and their son, Melaku E. Bayen, Jr. There, he joined the Ethiopian Red Cross and assisted the wounded on the Eastern Front. When the Italian Army captured Addis Ababa, Melaku’s family went to England and later to the United States to fully campaign for Ethiopia.

Schooled in Pan-African solidarity from a young age, Melaku co-founded the Ethiopian Research Council with the late Leo Hansberry in 1930, while he was student at Howard. According to Joseph Harris, the Council was regarded as the principal link between Ethiopians and African Americans in the early years of the Italo-Ethiopian conflict. The Council’s papers are housed at the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University. At present, Professor Aster Mengesha of Arizona State University heads the Ethiopian Research Council. Leo Hansberry was the recipient of Emperor Haile Selassie’s Trust Foundation Prize in the 1960s.

Melaku founded and published the Voice of Ethiopia, the media organ of the Ethiopian World Federation and a pro-African newspaper that urged the “millions of the sons and daughters of Ethiopia, scattered throughout the world, to join hands with Ethiopians to save Ethiopia from the wolves of Europe.” Melaku founded the Ethiopian World Federation in 1937, and it eventually became one of the most important international organizations, with branches throughout the United States, the Caribbean, and Europe. The Caribbean branch helped to further solidify the ideological foundation for the Rasta Movement.

Melaku died at the age of forty from pneumonia he contracted while campaigning door-to-door for the Ethiopian cause in the United States. Melaku died in 1940, just a year before the defeat of the Italians in Ethiopia. His tireless and vigorous campaign, however, contributed to the demise of Italian colonial ambition in Ethiopia. Melaku strove to bring Ethiopia back into the African world. Melaku sewed the seeds for a “re-Africanization” of Ethiopia. Furthermore, Melaku was a model Pan-Africanist who brought the Ethiopian and African American people together through his exemplary work and his remarkable love and dedication to the African people.

Another heroic figure produced by the anti-war campaign was Colonel John Robinson. It is interesting to note that while Melaku conducted his campaign and died in the United States, the Chicago-born Robinson fought, lived, and died in Ethiopia.

Above: John Robinson

When the Italo-Ethiopian War erupted, he left his family and went to Ethiopia to fight alongside the Ethiopians. According to William R. Scott, who conducted thorough research in documenting the life and accomplishments of John Robinson, wrote about Robinson’s ability to overcome racial barriers to go to an aviation school in the United States. In Ethiopia, Robinson served as a courier between Haile Selassie and his army commanders in the war zone. According to Scott, Robinson was the founder of the Ethiopian Air Force. He died in a plane crash in 1954.

Scott makes the following critical assessment of Robinson’s historical role in building ties between Ethiopia and the African Diaspora. I quote him in length: “Rarely, if ever, is there any mention of John Robinson’s role as Haile Selassie’s special courier during the Italo-Ethiopian conflict. He has been but all forgotten in Ethiopia as well as in Afro-America. [Ambassodor Brazeal mentioned his name at the planting of a tree to honor the African Diaspora in Addis Ababa recently.] Nonetheless, it is important to remember John Robinson, as one of the two Afro-Americans to serve in the Ethiopia campaign and the only one to be consistently exposed to the dangers of the war front.

Colonel Robinson stands out in Afro-America as perhaps the very first of the minute number of Black Americans to have ever taken up arms to defend the African homeland against the forces of imperialism.”

John Robinson set the standard in terms of goals and accomplishments that could be attained by Pan-Africanists. Through his activities, Robinson earned the trust and affection of both Ethiopians and African Americans. Like Melaku, he made concrete contributions to bring the two peoples together. He truly built a bridge of Pan African unity.

It is our hope that the youth of today learn from the examples set by Melaku and Robinson, and strive to build lasting and mutually beneficial relations between Ethiopia and the African Diaspora. As we celebrate Black History Month in the United States, let us recommit ourselves to Pan-African principles and practices with the sole purpose of empowering African people. The Ethiopian American community ought to empower itself by forging alliances with African Americans in places such as Washington D.C. We also urge the Ethiopian Government to, for now, at least name streets in Addis Ababa after Bayen and Robinson.

I would like to conclude with Melaku’s profound statement: “The philosophy of the Ethiopian World Federation is to instill in the minds of the Black people of the world that the word Black is not to be considered in any way dishonorable but rather an honor and dignity because of the past history of the race.”

To further explore the history of Ethiopian & African American relations, consult the following texts:

• Joseph E. Harris’s African-American Reactions to War in Ethiopia 1936-1941(1994).

• William R. Scott’s The Sons of Sheba’s Race: African-Americans and the Italo- Ethiopian War, 1935-1941. (2005 reprint).

• Ayele Bekerie’s “African Americans and the Italo-Ethiopian War,” in Revisioning Italy: National Identity and Global Culture (1997).

• Melaku E. Bayen’s The March of Black Men (1939).

• David Talbot’s Contemporary Ethiopia (1952).

—

In Pictures: Harlem Rekindles Old Friendship With Ethiopia

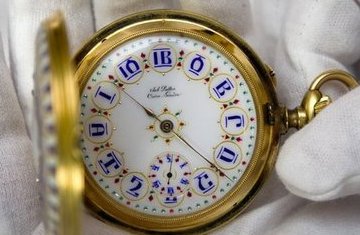

This photograph of Emperor Haile Selassie was presented by Abyssinian members as an appreciation gift to Reverend Butts. (Photo: Tadias)

Tadias Magazine

By Tadias Staff

November 6, 2007.

New York - Members of Harlem’s legendary Abyssinian Baptist Church congregated together on Sunday, November 4th to describe their recent travel to Ethiopia and to brainstorm ways in which they could play a meaningful role in the nation’s economic and social development.

It was the first time that the group had met since their return from their historic trip. The church sent 150 delegates to Ethiopia this fall as part of its bicentennial celebration and in honor of the Ethiopian Millennium.

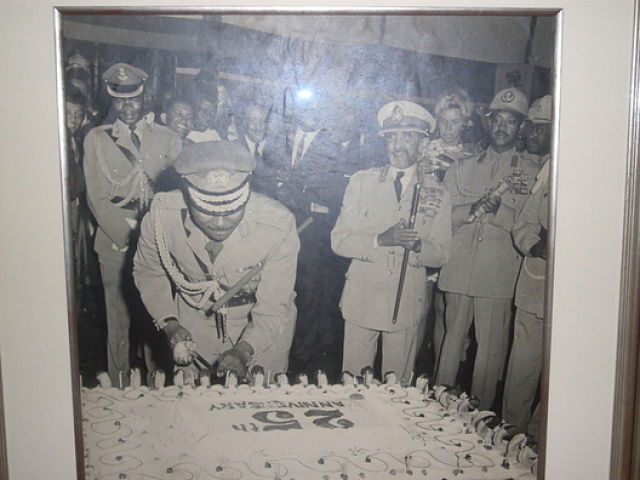

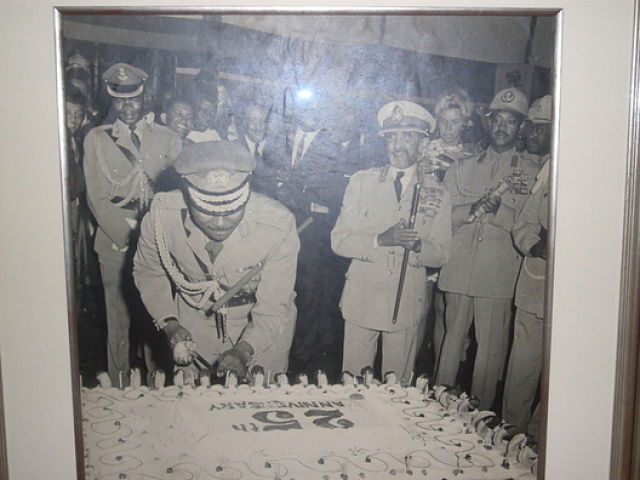

The meeting officially opened with Abyssinian members presenting an appreciation gift to Reverend Butts – a photograph of Haile Selassie, which they believe to be the Emperor celebrating the 25th anniversary of his reign. The photo had recently been purchased in Addis Ababa, after having been discovered lying covered in dust in a back room at one of the local shops (souks), according to church members who presented the gift.

Reverend Butts thanked the members and reiterated how much he enjoyed his stay in Ethiopia. “We are focusing on Ethiopia,” Butts said, “because our church is named after this nation. We also believe that Ethiopia is the heart of Africa. What happens here may be replicated elsewhere on the continent. It is the seat of the African Union.”

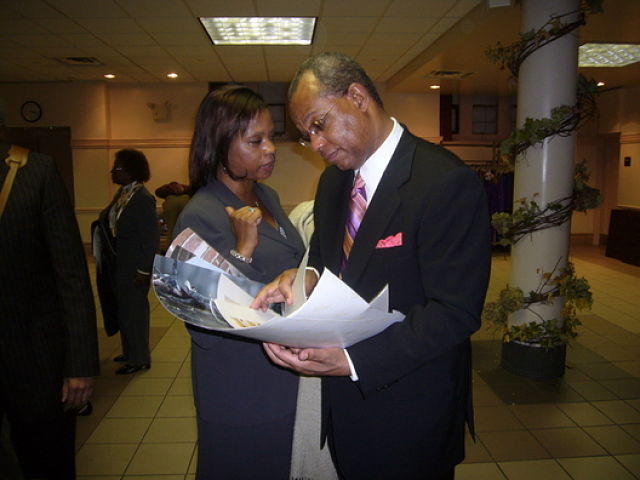

Raymond Goulbourne, Executive Vice President of Media Sales at B.E.T. He is already thinking about purchasing a home in the old airport area of Addis Ababa and starting a flower farm business with Ethiopian partners. (Photo: Tadias)

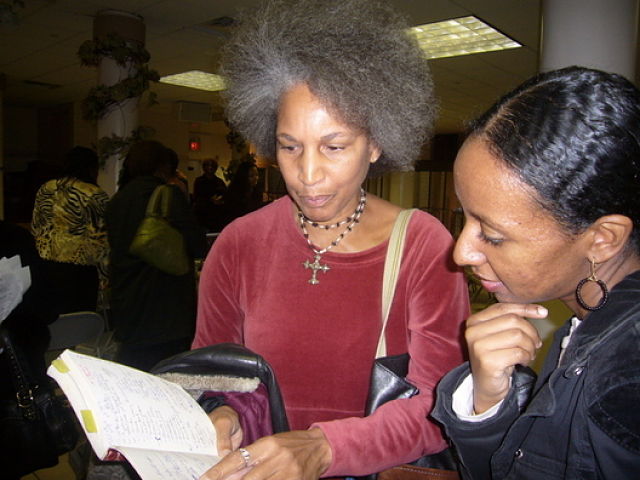

Adrienne Ingrum, Publishing Consultant and Book Packager, chats with Tseday Alehegn, Editor of Tadias Magazine. Ms. Ingrum is working on a proposal to create a writers cultural exchange program. (Photo: Tadias)

Both local Ethiopian media and the U.S. press had given coverage to the congregation’s two-week journey. While in Ethiopia, Reverend Butts received an honorary degree from Addis Ababa University. The celebration included liturgical music chanted by Ethiopian Orthodox priests, manzuma and zikir performed in the Islamic tradition, and Gospel music by the Abyssinian Church Choir.

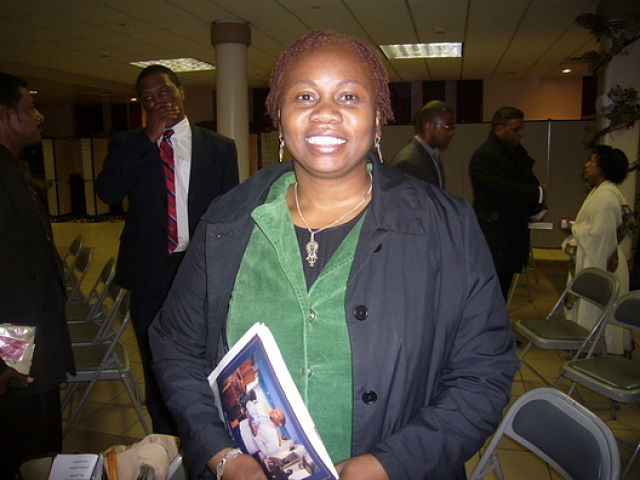

Jamelah Arnold, member of the Abyssinian Baptist Church delegation to Ethiopia. (Photo: Tadias)

The Abyssinian Church members visited schools, hospitals and NGOs in addition to touring towns and cities in Northern Ethiopia and Addis Ababa.

As they discussed various charity work, Reverend Butts encouraged the group to brainstorm ideas on how to make the maximum impact through volunteer work guided by the Abyssinian Baptist Church. Reverend Butts also shared the invitation that he had received from the Ethiopian Government to make a second group trip back to Ethiopia with the intention of meeting business men and women with whom they could start joint business ventures.

“We should think about the economic impact that our trip has made – we have invested close to $8 million dollars and we focus not just on charity but also on developing business opportunities.”

A spokesperson from the Ethiopian Mission to the United Nations addressed the group and mentioned the recent reorganization of Ethiopia’s foreign ministry, which now includes a “Business and Economy Department” that focuses on joint business ventures.

Ethiopian-American social entrepreneur Abaynesh Asrat (middle), Founder and CEO of Nation to Nation Networking (NNN), accompanied the group during their Ethiopia trip. (Photo: Tadias)

In addition, an initiative to involve more youth in volunteer work in Ethiopia was presented. Possible charity work suggested by the Abyssinian Baptist Church members included providing soccer uniforms for a team in Lalibela, assisting NGO work in setting up mobile clinics, aiding priests in their quest to preserve and guard ancient relics, creating a writers cultural exchange program, providing young athletes with running shoes, and improving education and teacher training.

Reverend Butts reminded the audience that civic participation is also another avenue that the church could focus on.

“Our ability to influence public policy – this too will be a great help to Ethiopia,” he said.

“We should write our congressmen and senators and let them know that we’re interested in seeing economic and social projects with Ethiopia’s progress in mind.”

Brenda Morgan. (Photo: Tadias)

Sheila Dozier, Edwin Robinson, and Dr. Martha Goodson. (Photo: Tadias)

Reverend Butts thanked his congregation for sharing their ideas and experiences and expressed his hope to once again make a return pilgrimmage to do meaningful work in Ethiopia. Perhaps, even set up a permanent center from where the work of the Abyssinian Baptist Church could florish from one generation to another.

In 1808, after refusing to participate in segregated worship services at a lower Manhattan church, a group of free Africans in America and Ethiopian sea merchants formed their own church, naming it Abyssinian Baptist Church in honor of Abyssinia, the former name of Ethiopia.

In 1954, former Ethiopian Emperor, Haile Selassie I, presented Abyssinian’s pastor, Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., with the Ethiopian Coptic Cross. This cross has since become the official symbol of the church.

—

Related:

Spotlight: The Chicago Defender, One of America’s Oldest Black Newspapers

President Obama Becomes First Sitting U.S. President to Visit Ethiopia

Join the conversation on Twitter and Facebook.

Founded by artist Yenatfenta Abate, the 'Free Art Felega' project offers a platform for Ethiopian artists of various disciplines internationally to display their work as well as to discuss, exchange ideas and learn from each others experiences. (Courtesy photo)

Founded by artist Yenatfenta Abate, the 'Free Art Felega' project offers a platform for Ethiopian artists of various disciplines internationally to display their work as well as to discuss, exchange ideas and learn from each others experiences. (Courtesy photo)